This February I have decided to read books around a certain theme namely: Forensics. So welcome to Forensic February! The books I will write about in the remainder of the month all have something to do with Forensics (they have little to do with February, but I love alliteration, so you might also want to brace yourself for Memoir March….)

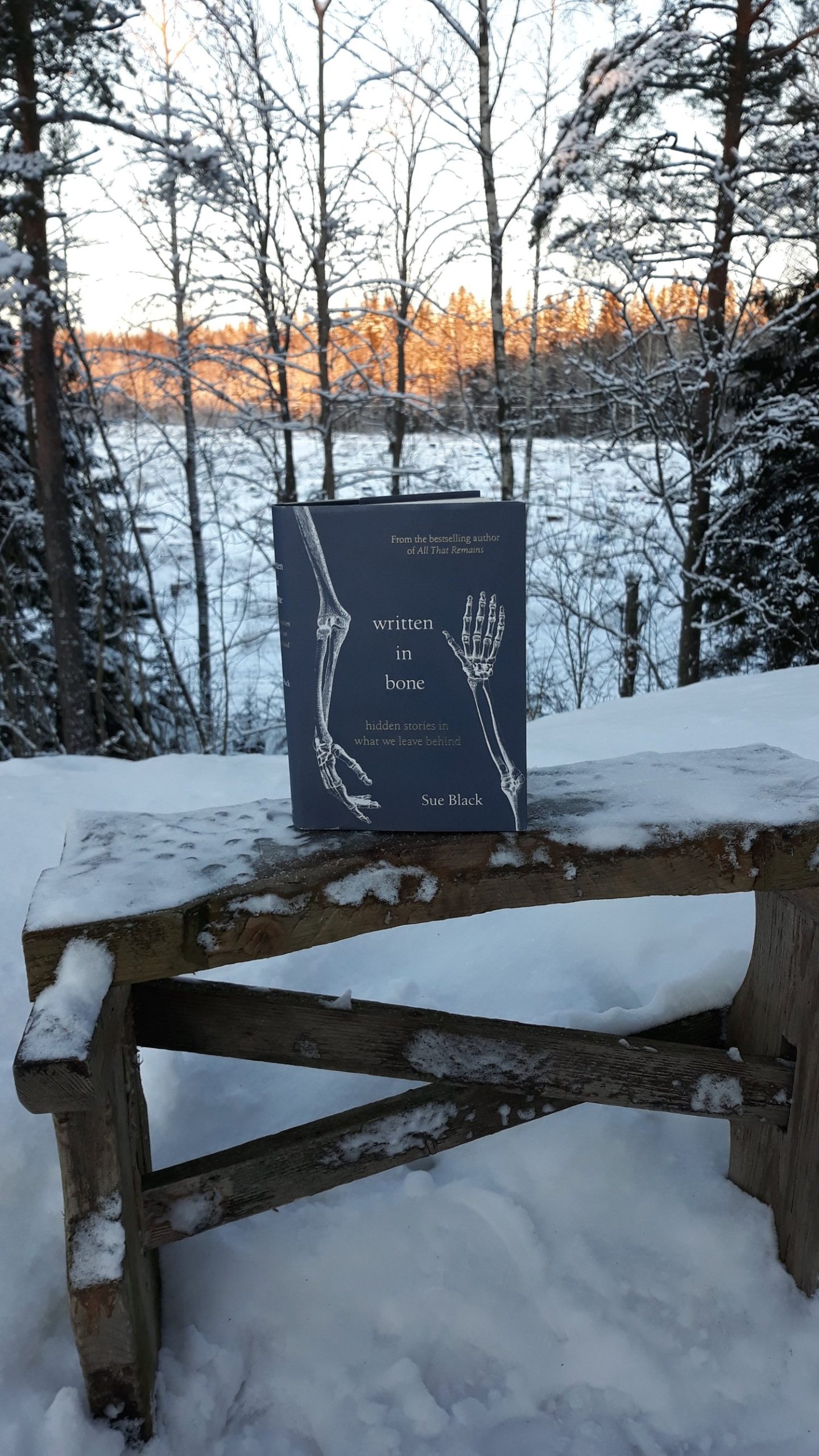

In Written in Bone: hidden stories in what we leave behind Professor Dame Sue Black takes us to the world of bones and forensic anthropology. I’ve had the pleasure of hearing Black deliver a keynote at the 14th edition of the Death, Dying and Disposal conference in Bath in 2019, which means I was able to read this book, as well as her previous book All that Remains in her wonderful Scottish accent. In the talk, as well as in parts of the book she has a go at television shows such as Bones and the utter ‘twaddle’ they try to pass off as forensic anthropology.

You might be wondering: what is forensic anthropology? And how is it different to, for example, cultural and medical anthropology. In short as a Medical Anthropologist I know nothing about bones, and Black does a very great deal. Forensic anthropology is the study of the human, or the remains of the human, for medico-legal purposes. Black writes:

“Forensic anthropology is a discipline that deals in the memory of the recent, not the historical past. It is not the same as osteoarchaeology or biological anthropology. We need to be ready to present and defend our thoughts and opinions in a courtroom as part of an adversarial legal process. Our conclusions must therefore always be underpinned by scientific rigour”

— Written in Bone Page: 14

Black stipulates that forensic anthropologists always need to address four issues when dealing with remains. The first question that needs to be answered seems blatantly obvious: are the remains human? Yet, Black gives a myriad of examples in which this might not be as straightforward as you think: seal flippers, when found on shores, are often mistaken for human hands. Also for the untrained eye it is very difficult to distinguish between bones from small animals and bones from children. The second issue is to establish whether the remains are of forensic relevance, as a discovered body might have been there for a while and may not have died because of foul play. A third question then is: who was this person? And lastly, can the forensic anthropologist decipher the cause and manner of death?

Forensic anthropologists are often brought to a scene, or presented with bones, to identify the identity behind this person. As forensic anthropologists are not always presented with a full skeleton, Black takes the reader through each part of the body, starting with the head and ending with the feet, and methodically tells us what each particular bone potentially can tell us about the identity of the person. And importantly, what the limits are of identifying a person with limited remains. Furthermore, even when presented with a full skeleton, the identity of a person may remain a mystery.

Forensic anthropologists need to be able to determine whether fractures in bones occurred pre, peri or post death. Forensic anthropologists are most interested in the fractures that occurred perimortem, or, around the time of death.

If you are interested in learning A LOT about bones than this is definitely the book for you. For example, did you know that bones are actually alive when a person is alive?! And that the skeleton renews itself roughly every 15 years?

“We are used to seeing bones as dry and dead, but while we are alive, so are they. If we cut them they bleed, if we break them they hurt, and then they will try to repair themselves to regain their original shape”

— Written in Bone Page:5

But this book is by no means a dry account (pardon the pun) on bones. Black has a wealth of fascinating anecdotes and a great sense of humour, so despite reading about horrendous crimes and ways of dying, it is not always heavy reading. My favourite anecdote is definitely the one where Black describes going to Italy to assist on a case were the identity of two heads had to be determined and the technique of superimposition was not available in Italy. Black thus had to take said heads back to Scotland to do a proper analysis.

“The heads were isolated frome the corpses and sealed in two plastic buckets. To further conceal their contents, each white bucket was placed in a carrier bag bearing the name of a well-known, high-quality Italian designer. The bags were unceremoniously handed over to me, together with two letters, one in English and one in Italian, explaining what I was carrying and that I had the authority to do so”

— Written in Bone Page: 79

Black travelled with the two heads as carry-on luggage on a plane (it might also be worth mentioning at this point that this was in the 90s) and successfully brought them to Scotland.

If these types of stories are your cup of tea, than you are in for a treat with Written in Bone. It is a great book for both forensic anthropologists and lay-people alike, as it offers an important and insightful ‘behind-the-scenes’ of the live of a forensic anthropologist and is stuffed to the brim with bone facts.

Have you read Written in Bone? Leave a comment below!

Leave a Reply