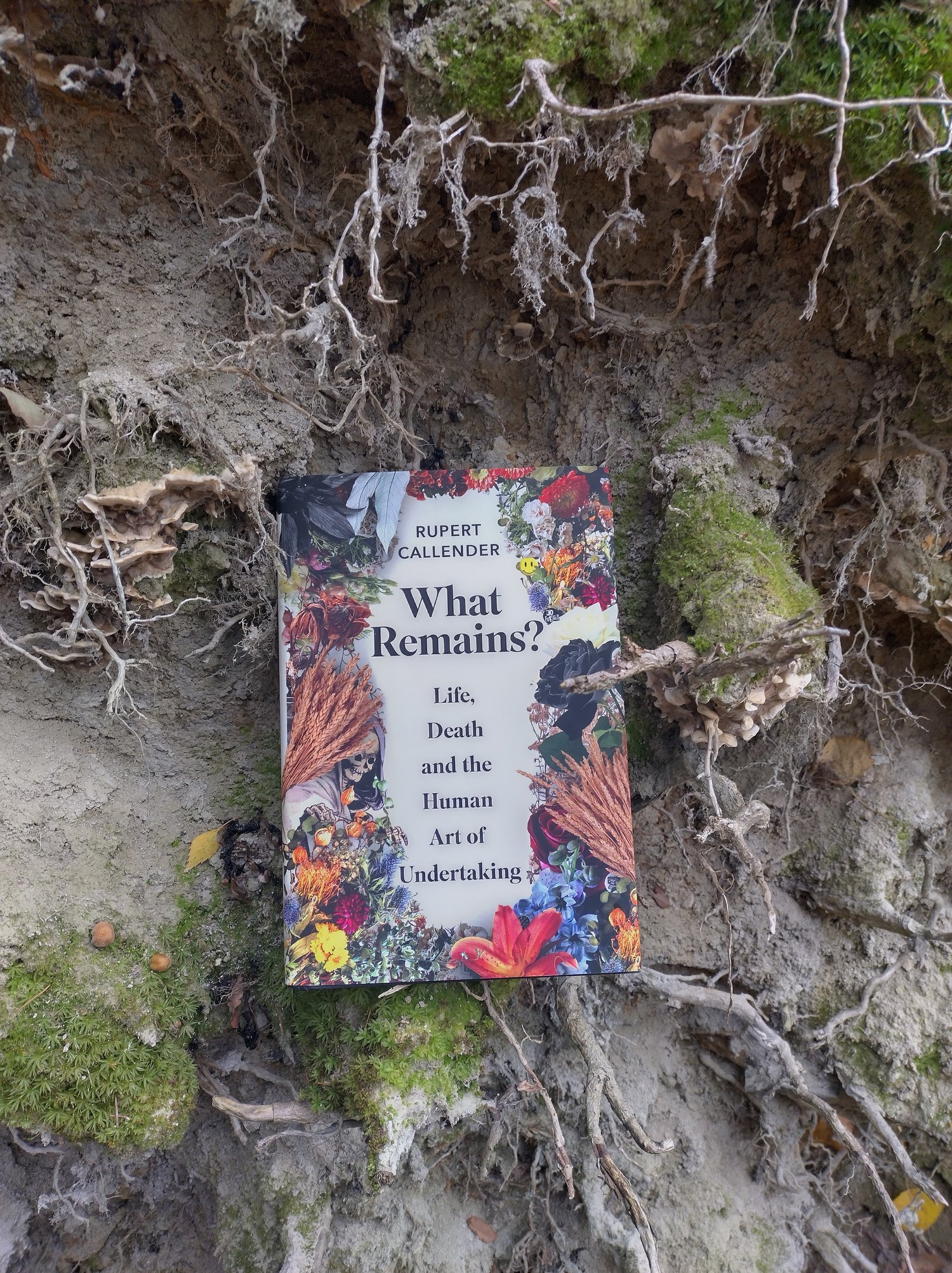

In What remains? Life, Death and the Human Art of Undertaking Rupert – Ru for short- Callender has written a polemic against the funeral industry. Not being part of his father’s funeral, who died when he was just seven years old, and being sent to boarding school that same year has left a bitter taste. Aged 25, his mother died; she had made all the decisions regarding her funeral arrangements herself and, again, he was not emotionally or even practically involved in shaping the ritual of burial. An unexpected five minutes of television compounded with his own experience, sparked a life-long interest and commitment to change the world of funerals. Seeing Nicholas Albery, co-founder of the Natural Death Centre on the screen, made something inside Ru click into place.

“The thing is, I wasn’t an introspective youth who had always dreamed of driving a hearse or putting make up on a corpse. I was a wounded young man, savagely mauled by bereavement from the age of seven and traumatised by the inadequate response of those around me to help me deal with it.”

— What Remains (Callender, 2022 page 12)

Last year I had the pleasure of talking to Callender twice. Once for a Dead Good Conversation (which I now wish we had recorded!) and once for The Death Studies Podcast, which is due to be released this year. He has been described as ‘the first punk undertaker’ although our conversations revealed that this label is more apt for his former partner Claire- he prefers ‘acid house undertaker’ as this underground scene has helped him, and perhaps even saved him.

What Remains? can be read as part manifesto, part memoir, part biography and as a love/hate relationship with death. Despite having worked with death for decades, Callender is not alright with death.

“Death is not my friend, neither is it my enemy; it is my destiny, and the knowing of that cannot but make me shake with fear and emotion.

But I would still hit it hard over the head with a shovel if I got the chance, if there was any alternative apart from immortality”

— What Remains? (Callender, 2022 page 22)

What Remains? will be a room splitter: some people will find it a breath of fresh air, that breaths new life into a stuffy funeral industry, others might find his anger misplaced or misdirected, or feel it is a world that shouldn’t be touched. Callender is clearly angry. I found some of Callender’s criticisms against the funeral industry repetitive (he certainly has a strong issue with pallbearers). I would have liked Callender to have acknowledged that “the UK funeral industry” is not as static or singular as he might have experienced it, nor is he the only one that critiques it. At times I was missing nuance, the grey area if you like. Admittedly, I have never attended a UK funeral, but the people that I know who work in the same ‘UK funeral industry’ all try their very best to create meaning and ritual in contemporary funerals. Surely they cannot all be exceptions? Importantly, some people might want all the “pomp and ceremony” in the world, including pallbearers- but let’s be honest, those people will likely not knock on Callender’s door for assistance.

What Remains? gives people permission to take more control over the funerals they plan, to let go of the old and in with the new. Callender has very clear ideas and visions of what funerals should look like. Preferring the term ‘undertaker’ over funeral director, Callender wishes to give power to the families and close circle of the person that died, in creating a meaningful ritual to say goodbye to the deceased. To Callender, taking time, having a so-called ‘slow’ funeral, and involving the body are paramount elements of a good funeral. Undoubtedly also shaped by the death of his own mother, Callender strongly believes that the funeral is very much for those who stay behind:

“Say what you have to say while you live, but let go of the bit right after. Let your family and friends decide what is said about you. They know a side of you that is impossible for you to know yourself, and they need to acknowledge that side and say goodbye to it. It’s their work, their grief, their loss, not yours.”

— What Remains? (Callender, 2022 page 51)

You may not agree with Callender’s vision, but one of the great things about writing that strongly advocates a certain point of view is that it clarifies your own: if you are offended, wrongfooted or upset by some of the statements made by Callender, this offers great opportunities to unpack why you feel this way. Personally, I find the ‘don’t insert yourself in your own funeral’ a bit to black and white, but this is also shaped by my own experience of my mother often announcing that she wants to have a certain song at her funeral if she hears it on the radio, or when we discuss death (which admittedly we probably do more than other families) – while she has not been directing all the ins and outs of her own future funeral (her personal goal is to live to be 100, so that is still a long way away), I find it comforting to know that the songs of Janis Joplin and Melanie will be part of the ceremony.

Callender’s descriptions of working with some of the families were some of the most meaningful passages of the book. As there is no set script to the funerals that Callendar co-creates, the close circle gets to decide for themselves how they wish to start and finish a funeral. As an avid reader myself, I found his descriptions of working with a family where the mother died, and how the son literally bookended the ritual, incredibly moving:

Julie’s son decided what we would do. After he, his dad, his sister and a family friend had lowered Julie down into her grave, Tommy pulled up a chair beside her grave and sat down. He had been reading to her as she died, but she had died before the end of the book. There were still four pages left. That boy took out the book and lovingly read it out loud to his mother. We all stood around him, eyes wide with tears, shaking with emotion. When he had finished the book, he put the book down, stood up, took off his jacket and picked up a spade. He and his father started to fill the grave.

-What Remains? Callender 2022, page 192.

I understand some of Callender’s gripe against the industry, and all the pages are seeped with his own grief, but I would have loved to have read more of the stories of the families he has worked with, as this brings to light the importance and impact of the work that he does.

I think Callender’s book is like marmite: either you love it or you hate it, and I would love to know which side of the spectrum you fall on! It has definitely given me lots of food for thought and has challenged some of my own assumptions and sharpened some of my own ideas.

If you haven’t read it, but would like to buy a copy, you’ll be happy to hear Chelsea Green is currently having a summer sale and it is half price.

Leave a Reply