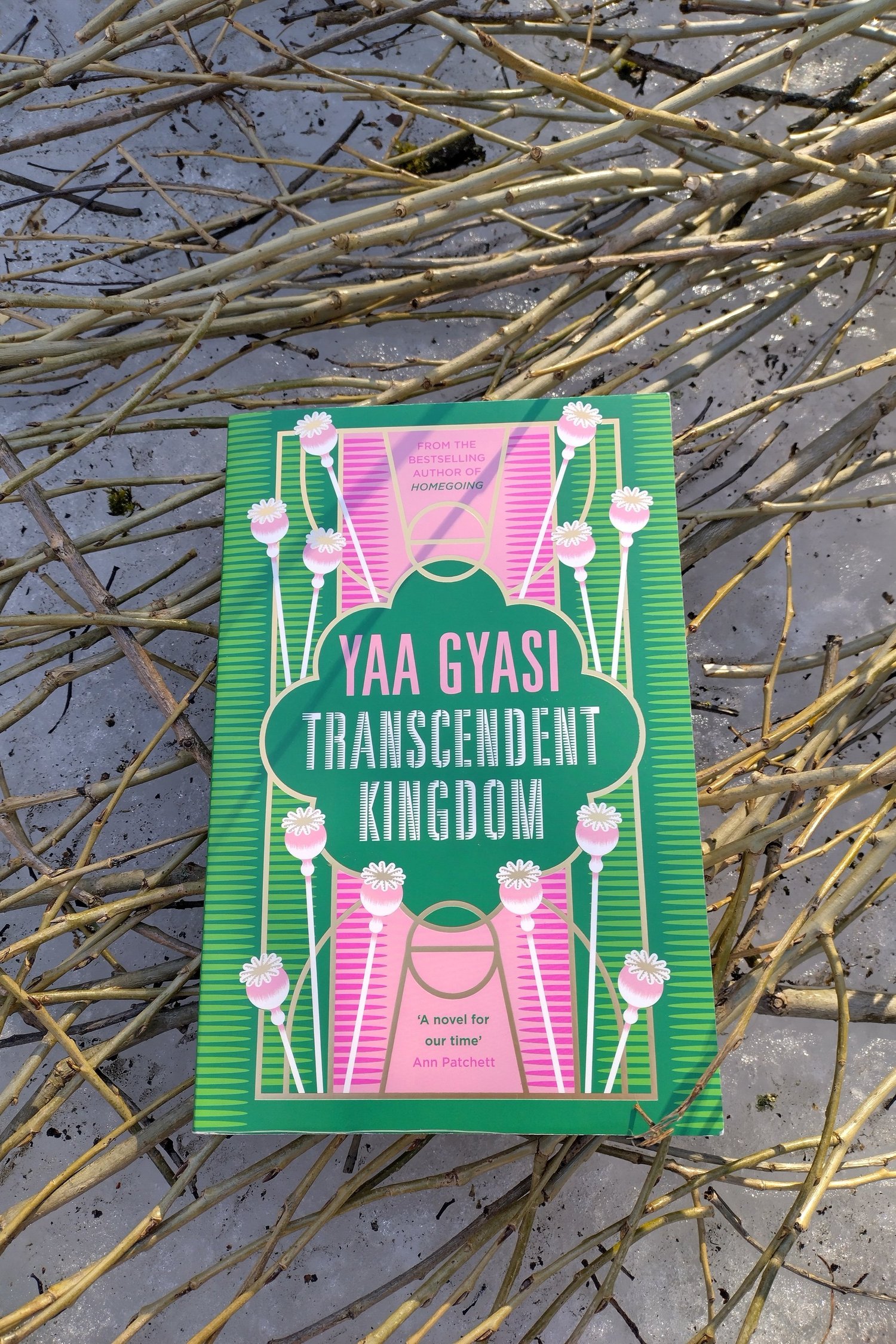

They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover but just have a look at the cover art of Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi! Her debut Homegoing had an equally gorgeous cover and, more importantly, a story line that gripped my from page one. So when I heard Gyasi published a second book I instantly rushed to the book store to get my hands on a copy, for it to subsequently gather a lot of dust on my shelf, as I do have a slight book-buying addiction. I am a strong believer that some books just need to sit on a shelf, for the reader to get ready to delve in (and yes, this might be me justifying my own addictive behaviour).

In Transcendent Kingdom we follow Gifty, a PhD researcher in neuroscience at Stanford interested in addictive behaviour. For her doctoral research she conducts experiments with mice, to try and understand why some mice (and by extension people) keep returning to a lever that initially would give them a reward, but now just gives them an electric shock. Why do they keep returning to something that brings them harm? Why don’t they stop pressing the lever?

I am a strong believer that most academic research comes, in part, from a personal connection to the topic and, albeit a fictional account, this is also the case for Gifty. Gifty’s brother died of an overdose as a teenager. But this is not the story of a poor Black boy, raised by a single mum who has inevitably fallen into bad ways. This is the increasingly common story of people being prescribed strong opioids to help them recover from an injury. So yes, Nana was a poor Black boy raised by a single mum, but he was very apt at sports and had a very promising future. Until he hurt his ankle and was prescribed OxyContin. This prescription is the start of an addiction to pain killers, and the beginning of the end.

A recent report published by the Lancet predicts that another 1,2 million people will die of an opioid overdose if prescription practices don’t change. This is an exponential growth of deaths and shows that Gyasi’s fictional account does not describe an isolated incident, but instead sheds light on a growing epidemic. Reading Transcendent Kingdom through my European lens, I was surprised to read how an ankle injury would get you an oxycodone prescription, but then I also think we tend to err on the side of caution in the Netherlands (and Finland) and try to cure everything with paracetamol or ibuprofen.

Gifty’s mother cares for older people, and is therefore very familiar with the presence and sound of dying. Nana’s addiction prompts her to prepare her children for the sound of dying, and the reality of death.

“Because really, it wasn’t Mrs. Palmer’s death that I was afraid of; that wasn’t the reason my mother had started trying to teach us about the sound and the relief of pain. I was scared for Nana. Scared of Nana and the death rattle that none of us wanted to acknowledge we were listening for”

— Gyasi Page:157

Gyasi skilfully weaves past and present together; she alternates childhood memories of Gifty and Nana with the aftermath of Nana’s death. For Gifty, this experience probably sparked her interest in understanding addictive behaviour and trying to find a cure (and likely also a means to travel back in time to safe her brother). For Gifty’s mother, this triggers several bouts of mental health problems. The first one so bad, that shortly after her brother’s death, Gifty is send to family in Ghana, as her mother is committed to a psychiatric ward.

But we arrive in the story post Nana’s death, when Gifty is already embarking on her doctoral studies. Her mother visits her, only to lie down in bed and not rise from it. We thus see two very different responses to grief: one person throws themself into their work; and the other is literally unable to move and function. Both depression and escaping into work are common grief responses.

“All of the self-help literature I’ve read says that you have to talk about your pain to move through it, but the only person I ever felt like I wanted to talk about Nana was my mother and I knew she couldn’t handle it”

— Gyasi Page: 171

Gifty’s experience shows the difficult bind siblings can be in the aftermath of the loss of a sibling. In her case, a role reversal takes place where she becomes in many ways the parent, and her mother becomes the child. Having read quite a few memoirs these past months, including Cathy Rentzenbrink’s The Last Act of Love, which also centres around sibling loss, it is difficult not to read Gyasi’s one as one as well. Her writing his convincing and moving, and like Homegoing, Gyasi’s characters in Transcendent Kingdom have a level of depth and complexity that is very engaging and powerful to read. I for one, am looking forward to whatever Gyasi writes next.

Leave a Reply