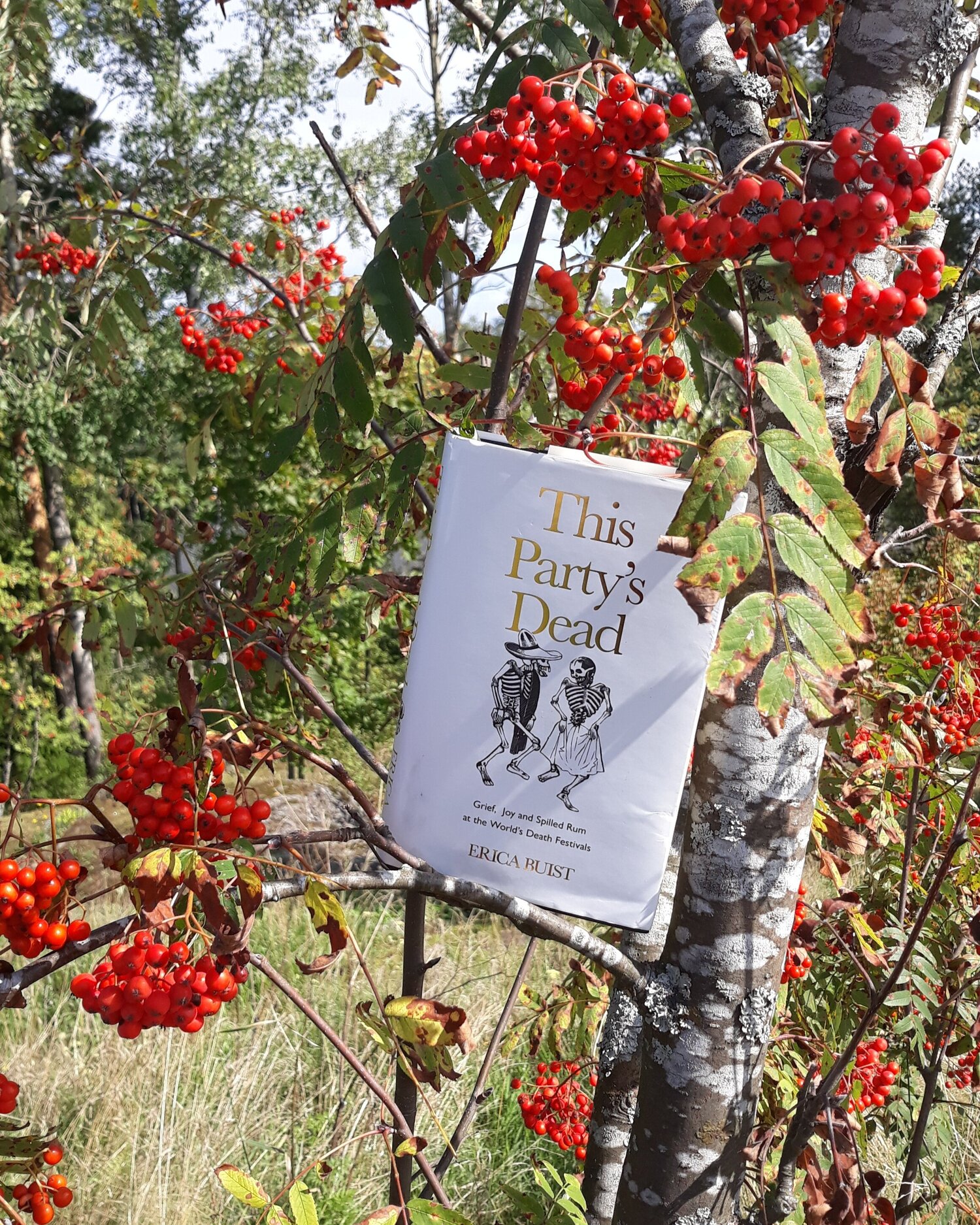

As a Death Scholar, I have to admit that reading the synopsis of This Party’s Dead. Grief Joy and Spilled Rum at the World’s Death Festivals made me real jealous, real fast. Visiting death festivals around the globe sounds like a dream holiday. The reason Erica Buist started this endeavour was not a cheerful one, as this journey was a direct response to the death of her father-in-law. He died at home in his own bed, and was only found a week later. Buist took the loss hard, but found a very creative way to try and make sense of this loss:

““ ‘I’m going to go to seven festivals for the dead,’ I say.

His eyes widen. I’ve barely left the house in weeks, I failed to buy a sandwich in a supermarket 900 feet from my front door, and I’ve just announced I’m travelling to seven countries.

‘OK. Why seven?’

I pause. I look at my hands.

‘One for every day we didn’t find him’ ”

— This Party’s Dead. Page:54

Much of This Party’s Dead centres around the legitimacy of feelings of loss and grief, or what Kenneth Doka has called ‘disenfranchised grief’. This is grief that is not openly acknowledged, socially validated or publicly mourned. Whilst Buist does not explicitly use this term, her reflections clearly show that she was struggling with the legitimacy of grieving the loss of her father-in-law (or father-in-law-to-be). Her uncertainty of being ‘allowed’ to grief for someone she was not directly related to, and to feel guilty for feeling ‘worse’ than her partner all show the assumed hierarchies and acceptability of grieving a loss. This internal struggle of wondering whether it is acceptable to grieve is definitely not helpful in coming to terms with a sudden death. How people respond to a loss depends on the strength of a bond and the nature of the relationship, this means that one can ‘even’ grieve someone you’re “not supposed to”. I deliberately put this between quotations, as it is very dangerous to speak about death and loss in normative terms. If you liked someone when they were alive, you will most likely be affected by their death.

This also leads me to a second concept that, whilst similarly never mentioned, is at the heart of the book. This is the concept of ‘continuing bonds’. Continuing Bonds Theory emerged in the 90s and suggests that instead of ‘breaking a bond’ after death, people continue to have some sort of relationship with the deceased. All of the death festivals described in the book are a way for people to continue a bond with their deceased loved ones. A death celebration that probably receives the most attention in popular culture is dia de Muertos, or the day of the dead, in Mexico. In China they celebrate the dead with the Pure Bright Festival. In Tana Toraja, a remote area in Indonesia they celebrate Ma’neme, where dead relatives are retrieved from burial caves and dressed in new clothes. These are just some of the Death Festivals Buist visits, and they all show how people continue the bond with their deceased loved ones in various ways. Whilst it may appear that this continuing of bonds appears in ‘other’ places, Buist clearly uses this whole experience as a way to continue (and perhaps justify) the bond with her deceased father-in-law.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading This Party’s Dead but there is one criticism I have to offer which is: “the West” is not a place! I understand that Buist was trying to juxtapose two different ways of coping with death and loss, but I think she lost some of the nuance by arguing so strongly that “the West” does things differently compared to ‘other places’. Buist seems to conflate “The West”/Britain/England in her writing, thereby bypassing the diversity of ways that people in the so-called ‘West’ deal with death and dying. England is often stereotypically portrayed as a place where death is ‘taboo’ or not spoken about, but having conducted research in England for the better part of a decade I tend to disagree. Perhaps death and dying is not something to be discussed with friends and family, yet I have found ‘the English’ very comfortable in talking about death and dying with me as a researcher/outsider/stranger. Buist explicitly mentions that SHE is terrified of death and dying and losing people in her life, and I think the book would have worked just as well, if not better, if that had been her main argument. People who know me also know I am allergic to any usage of the term “the West”, which betrays my background in anthropology, where this criticism was emphasised over and over again from day one. This criticism is thus not necessarily directed at Buist as an individual but at a wider trend to compare ‘the West’ with ‘the Other’.

Having said this, I strongly encourage people to pick up this book and read it, as many people will identify with questions like ‘Am I supposed to feel this?’, ‘Is it OK if I feel/do this?’. I have definitely added some places to my bucket list to travel to when the world will open up again and can’t wait for whatever Buist writes next.

Leave a Reply