Happy 2023 everyone! I started this year off strong with the flu, which knocked me out (or at least my reading and writing abilities) for a good couple of weeks. But here we are, first review of the new year!

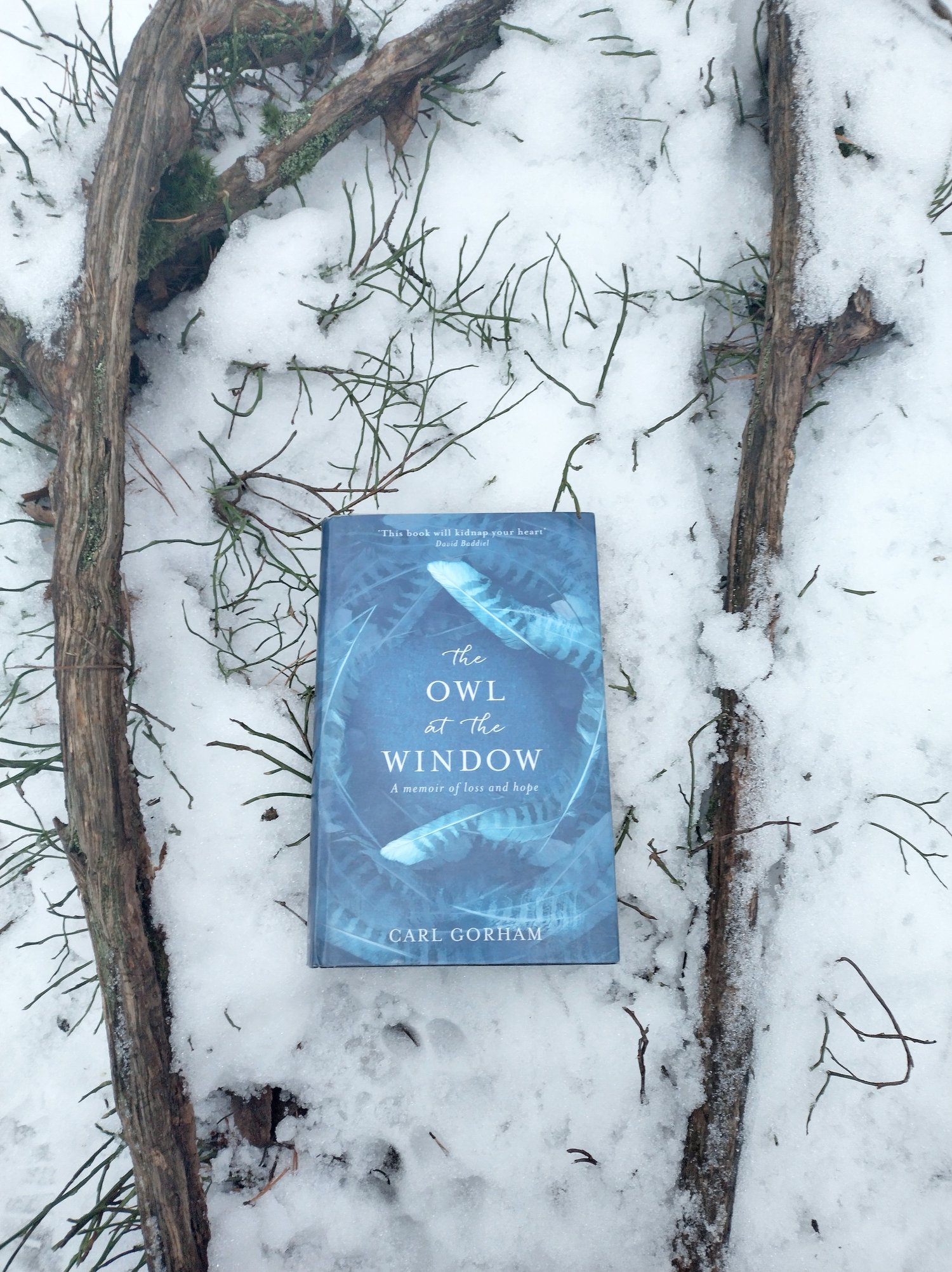

The Owl at the Window: a memoir of loss and hope by Carl Gorham is another wonderful addition in the long list of grief memoirs that I have read. My reading selection so far gives the appearance that women dominate this genre, but there are accounts like The Owl at the Window that show that men also sometimes engage in this type of writing.

This memoir fluctuates between past and present, with the chapters set in the past written in italic. The Owl at the Window is both Carl Gorham’s life story as well as his way of trying to make sense of his life as a widower and single father.

Our understanding of grief is strongly influenced by the ‘psy’ disciplines psychology and psychiatry. These disciplines offer a particular lens on grief and bereavement, sometimes seeing it as an illness, pathologizing certain behaviours and experiences of grief. There are many great therapists out there helping people working through their losses but they can also come with a particular set of words you might not be ready for when you are in the thick of your grief.

“‘ I think what I am looking for is … some sort of … expert … insight… or … er … support to help me through the whole grief process,’ I said

‘ The first thing I’d say Is that I strongly believe there is no grief process’

This was going to be trickier than I’d thought.

She continued, ‘A “process” implies there is a set series of things that you go through in order to emerge the other side and I don’t think grief is quite like that.’

‘Okay.’ I took a deep breath. ‘ I think I meant I wanted someone to give me a “map” of some sort.’

‘ I don’t think there is a map.’

‘ Or at least help me understand’

‘ That’s implying it’s understandable,’ she added.”

— The Owl at the Window (Gorham, 2017 page 76-77)

Gorham shows that seeking help, or dabbling in therapy is not easy and that the language of loss is complicated. You might not have the right words to express your grief, and the words you do have may well not be considered “appropriate”. The example above shows the complexity of language and grief. Academics and professionals might think deeply about the ‘right’ grief terminology, and while this is important, there should also be space for those experiencing grief to express themselves in whatever way they see fit.

I completely understand where the therapist cited above is coming from, but reading this I am also thinking ‘was this interaction really necessary at this point in time?’ – this unpacking of words could have been conversation number two. In retrospect, I hope that interaction was helpful for Gorham, but I can also feel the ‘are you joking?’ oozing of the page.

Another aspect of grief and loss that offers ample ‘are you joking?’ moments is the death admin that unfortunately comes with a loss. Gorham gives insight in the excruciating bureaucracy. You would think that announcing that someone is dead gives organisations enough reason to shut down a bank account but as the following excerpt shows, this is clearly not always the case:

“‘We would need to speak to her,’ says the bored voice.

‘You can’t,’ I reply.

‘Well, I’m sorry, sir, we won’t be able to close it unless we speak to her.’

‘But you can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘She’s dead.’

There is a long pause and the voice returns, as defiant as before, ‘Well, we still need to speak to her.’”

— The Owl at the Window (Gorham, 2017, page 82).

Obviously, there needs to be some proof that someone is actually dead, as it would be weird if people could willy-nilly cancel other people’s accounts, but conversations like the one above, and another conversation with a bank where Gorham is told that ‘a copy of a copy’ of the death certificate is not acceptable proof, all show that these processes clearly do not have the best interest of bereaved people at heart.

Finding himself the single father of a six-year old is not without challenges. Gorham worries a lot about the way his daughter is coping with this new reality. At the request of his daughter, they craft a ‘cardboard mummy’, which for a long time is treasured by Romy. This object is integrated in the everyday routine, spoken to and sits at the dinner table. When Romy asks for ‘cardboard mummy’ to join in their shopping trips doubt sets in whether this is the ‘right’ thing to do, mainly because of the potential responses of the outside world to cardboard mummy. This prompted me to remember that like Romy, I spoke to an inanimate object after the death of my uncle when I was nine. It was a clay teddy-bear Christmas ornament and it lived in a wooden winebox that I had filled with kitchen paper with pretty prints (yes, I was easily wowed as a child and collected kitchen paper for a while). The teddy bear ornament lived in the box and I would often speak to it at night, in a way to speak to my uncle. I am not sure I have ever told anyone that I did this, but like Romy, at some point I no longer felt the need to do this.

The Owl at the Window is a lovely memoir that shows insight into the complexities of widowhood, single fatherhood and the minefield that is grief.

To learn more about Carl Gorham, visit his website

Leave a Reply