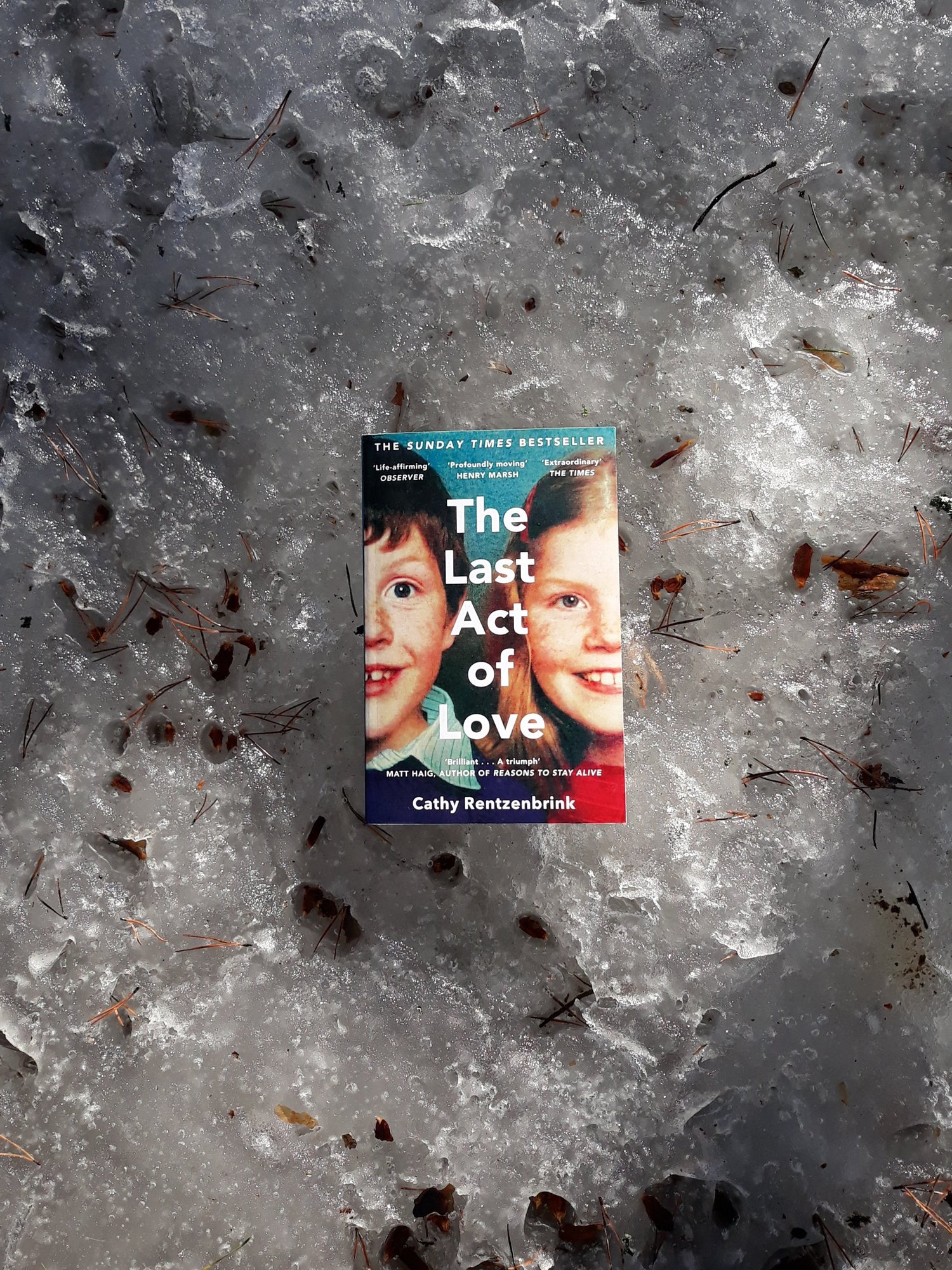

Last year a book about books caught my attention. In Dear Reader: the comfort and joy of books Cathy Rentzenbrink talks about her relationship with books and how they very much bring her joy but, pertinently, how they helped her escape her own life after her brother was hit by a car and lived in a liminal state between life and death for the next 8 years. In my review I joked that I had picked the least ‘deathy’ book Rentzenbrink had written; and also that since Helsinki Library doesn’t hold I copy I was ‘willing’ to receive a complementary copy. And lo and behold, Rentzenbrink actually read my little blog and offered to send me the Last Act of Love!

I sometimes worry that some of the off hand comments I make are in poor taste, especially when death, grief and loss are involved, but having just finished reading The Last Act of Love I think Rentzenbrink and I share the ability of finding humour in sometimes not really funny moments (but really they are, if you think about it).

The Last Act of Love was supposed to be included in my Memoir March selection, but March got the better of me. My sense of time has definitely altered since the start of the pandemic and I was convinced we had another week left. Yet here we find ourselves already in April. But as this is my blog, there are also my rules! So this week I will write about both the Last Act of Love and later this week about Rhiannon Spurgeon’s Grief Without Guilt to round off Memoir March. I must admit Memoir April doesn’t have the same ring to it, so please imagine we are still in March.

Cathy Rentzenbrink’s carefree teenage years stopped abruptly the night her brother was hit by a car. Matty was just 16 years old, Cathy a year older and aged 17. At the night of the accident Cathy finds herself in the chapel of the hospital, and whilst not religious, she is praying for her brother’s survival.

“What strikes me now as it never has before is that I can’t say my prayers went unanswered. I was given what I asked for. My brother did not die. But I did not know then that I was praying for the wrong thing. I did not know then that there is a world between the certainties of life and death, that it is not simply a case of one or the other, and that there are many and various fates worse than death.”

— Rentzenbrink Page:3

Matty did survive the car accident, but afterwards was in a permanent vegetative state. Rentzenbrink admits that she and her family did not fully understand what this meant at the time, and whether care professionals fully explained this to them. For a long time they were hopeful for recovery, clutching to stories about people awakening from comas after years and years. But Matty did not recover. He did not get better.

For years, Rentzenbrink and her parents became full time carers of Matty. Rentzenbrink’s mother talks about experiencing bereavement without death. Whilst Matty did not die, he was clearly not the Matty before the accident. This was an ambiguous loss as they where grieving someone who was still alive, yet unable to participate in life, unable to express wishes, needs and emotions.

Matty’s case is rare. Not many people are in a permanent vegetative state (PVS). The case of withdrawal of care for Tony Bland, who was in a PVS after the infamous accident at Hillsborough football stadium, brought the possibility for Matty to actually die to the fore. It still took years for Rentzenbrink’s mother to come to terms with the possibility of withdrawing food, drink and medicine so Matty could die. The law has changed since, but Rentzenbrink’s family had to file a court case against her brother to apply for the withdrawal of care. It is this case that is their families ‘last act of love’. As Rentzenbrink’s mother writes in her affidavit:

“I have known for some time that there is nothing I can do for Matthew to enrich his life in any way. He needs to die. We had hoped it would happen with an infection and withouth the need to approach the court. But the sad irony is that his poor body, unable to do anything else, seems capable of fighting infection. So we are asking the court’s permission to cease nutrition and hydration so that Matthew can be released from his hopeles state. It is our last act of love for him.”

— Page:143

These days it will be healthcare providers making this appeal, moving the burden of such a difficult and heart-breaking decision away from a person’s family. The court granted the family’s request and after being PVS for 8 years Matty was finally allowed to die.

Rentzenbrink shows the challenges of experiencing sibling loss, particularly the ambiguous nature of this loss. Whilst she was experiencing a lot of anticipatory grief when Matty was in a liminal state between life and death, him actually dying was not a simple conclusion of the story, but instead the beginning of another difficult chapter.

In death and grief there is is a hierarchy of losses, albeit real or imagined: there will be deaths that are societally valued more than others, and individually we will have ideas of what we imagine are ‘worse’ or ‘better’ losses. Losing a child is pretty high up that list and often described as ‘the worst thing that can happen to a parent’. In this narrative, most of the space to grieve is given to the parents of the child. Importantly, what is often absent in this narrative is the space for ‘the other children’. Siblings tend to be absent in this story, whereas they are also profoundly impacted by such losses. Rentzenbrink shows how people tended to ‘spare’ her parents or didn’t want to bother them with questions, whereas she was not given this privilege and had to field all of those inquiries.

The Last Act of Love is the story of the sibling. The one that is left behind. The one that could have been the one who died, but didn’t. A profound sense of survivor guilt oozes from the pages. Rentzenbrink doesn’t use this term, but being the sibling that is still there comes with immense struggles: Anger. Grief. Frustration and lots of guilt. Also happiness sometimes, but then more guilt about experiencing happiness. This book is a well-rounded account that will be a breath of fresh air for those who lost a sibling and felt alone in their feelings. This type of loss is a story that people will carry with them their entire lives, as there are milestones the absent sibling will continue to miss. Grief will always be a story line when you a big love in your life dies. Rentzenbrink shows the difficulties of this ongoing narrative. She doesn’t promise it will get easier or that it will disappear, but that you will become more adept at carrying it and, importantly: your are not alone.

Leave a Reply