Disclaimer: I am currently recovering from Covid, which has caused some brain fog, so apologies if this review isn’t coherent…

Close your eyes. I want you to picture a widow. Who do you see? What do they look like? How do they move? What do they wear? What is their story? Take a moment to really think about this.

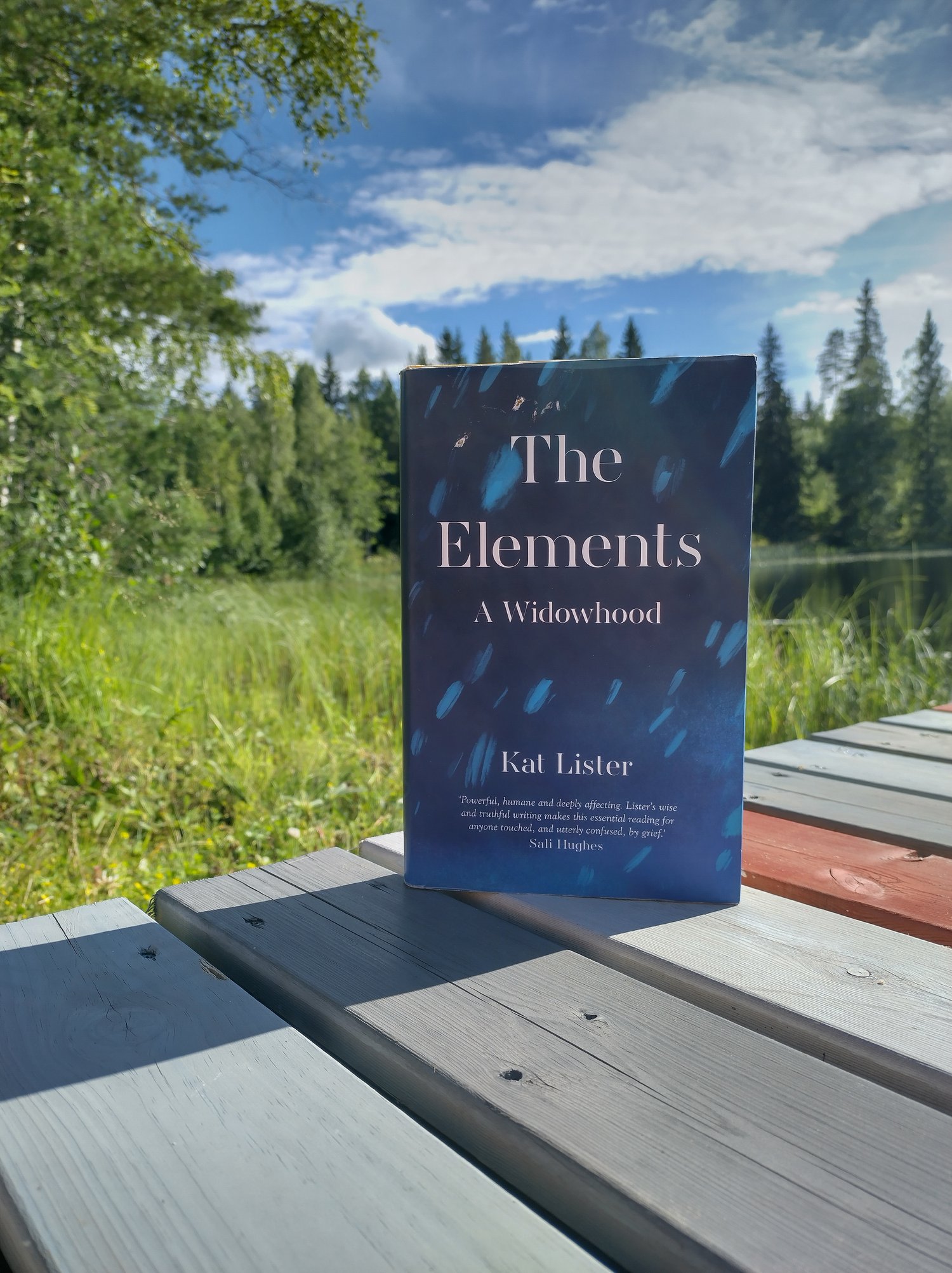

Open your eyes. How old where they? Did they have grey hair? It is unlikely you pictured the image of author and journalist Kat Lister who became widowed at the mere age of 35. In The Elements: a Widowhood Lister tells her story of losing her husband in her mid-thirties. Till death do us part came way too soon. Having just turned 33 myself, I cannot imagine losing my partner two years from now. One does imagine a future that stretches well into people’s 70s, 80s or perhaps even 90s.

Kat Lister takes readers through the four elements: fire, water, earth and air. She finds comfort in literature, or tries to make sense of her story through the written accounts of others, bot fictional and non-fictional. Fictional depictions of widowhood in particular, do not always match her own experience. Lister notes that Miss Havisham, a character in the Charles Dickens novel Great Expectations, who famously spends the rest of her life in her wedding dress, is often depicted as an older woman, whereas Dickens himself writes that Miss Havisham is in her mid-thirties. The ageing of Miss Havisham in popular depictions cements the notion that widowhood is something for old age.

“Literature teaches us that there is romance in death. Juliet isn’t the only female protagonist whose grief and trauma lead her to an extreme self-sacrificing deed. Anna Karenina throws herself onto the railway tracks and into the path of a speeding train. Madame Bovary opens a jar of arsenic. Come to think of it, most of the literature I read read in my impressionable teenage years was formed by the imaginations of men, so my understanding of grief was shaped by them, too”

— Kat Lister, The Elements (2021, page 13)

Literature shapes the way people think about death and dying, and the way certain experiences, like widowhood, are imagined. The authors of these stories may not always be people with personal lived experience of the stories they describe, and readers might not always recognize themselves in these words. Importantly, independent of the gender of the gender of the author (although it is quite problematic that many famous written examples of death and loss are written by men) some famous literary examples are arguably also quite dated as social phenomena like loss, grief and bereavement are always in flux.

Memoirs and non-fiction accounts of young widowhood are few and far between, and Lister’s account is a welcome addition to this literature. She personally ticks a lot of boxes in what I would like to see in a grief memoir. I am aware that I often read these books through quite an academic lens, but I am chuffed that Lister engages with a lot of academic grief literature, as this will break down barriers.

“Although any compulsion is hard to rationalise, many readers of my journalism have enquired about my urgent need to read as a way to process my trauma. In all honesty, I hadn’t considered my frenzied reading to be an unconventional act, or even a particular unusual one.”

— Kat Lister, The Elements (2021, page 20)

Bereaved people will be more likely to pick up Lister’s book than, for example, read academic papers on Continuing Bonds Theory, or Tonkin’s Model of Grief. An important notion that rarely is discussed in grief memoirs is sexual bereavement: the fact that you’ve not only lost a person, but also never will be able to be intimate with them. (Loss of) sexuality is an often neglected aspect of bereavement, as it is rarely written about, suggesting that above anything else talking about sex is way more taboo than talking about death and dying. Lister talks candidly about her personal challenges and doubts regarding this topic.

Lister acknowledges the cultural phenomenon that is the Five Stages of Grief theory, but also provides examples of critiques of this theory, such as Ruth Davis Koningsberg book The Truth About Grief: The Myth of Its Five stages in which Koningsberg notes that the decade the theory was introduced was also the time of a growing self-help movement and a growing void left by the reduced influence of religion. The grief theories mentioned in her book will invite readers to further investigate them themselves, if they do so desire. (And I will mention Grief Demystified by Caroline LLoyd again, as this is an excellent starting point).

“It would take time for me to realise that grief is anything but linear, that there are no stages to be ticked off, only motion sickness, as you careen from one mood to the next, desperately trying to mimic some semblance of everyday life. As a consequence, my memory of this time is pretty sketchy and it isn’t always something I can fully trust. My prose might seem assured, but the retrospection is flawed. Grievers aren’t always the most reliable narrators. ”

— Kat Lister, The Elements (2021 page 38-39)

The Elements is a wonderful mix between Lister’s personal story and her engagement with literature. We learn about Lister’s husband and his cancer diagnosis. How for years Lister’s life revolved around being a carer, around hospital appointments, seizures, uncertainty and fear. She talks honestly about how she had not anticipated that after her husband’s death she had to unlearn a lot of the habits and routines that came with being a carer, and that it was difficult to return to being a non-carer, or simply just a person trying to live a “normal” life.

Lister writes about the dilemma of wanting to have children, and the challenges of trying to become pregnant when your husband is being treated for cancer, and he might not be present in your hypothetical child’s life. She outlines the complicated pains of miscarrying in an emotionally already difficult time.

I do have one small criticism, that goes beyond Lister’s writing. Unlike academic books, non-fiction memoirs like these are rarely indexed and often do not have a bibliography. There are so many books mentioned in this memoir, that it would be helpful to have a comprehensive list at the end so book worms, like myself, can easily select their future reads. I have discovered that I often overestimate my memory, and will belief I will be able to remember titles afterwards, but nothing is further from the truth. My memory can be like a sieve. So again, this is not a criticism directed at Lister, but more a plea to publishers to include a bibliography in these types of books!

The Elements is a book I will definitely return to in the future. It will appeal not just to young widowers but to many people trying to make sense of their grief.

Kat Lister recently appeared on the Griefcast and you can listen to her episode here.

Leave a Reply