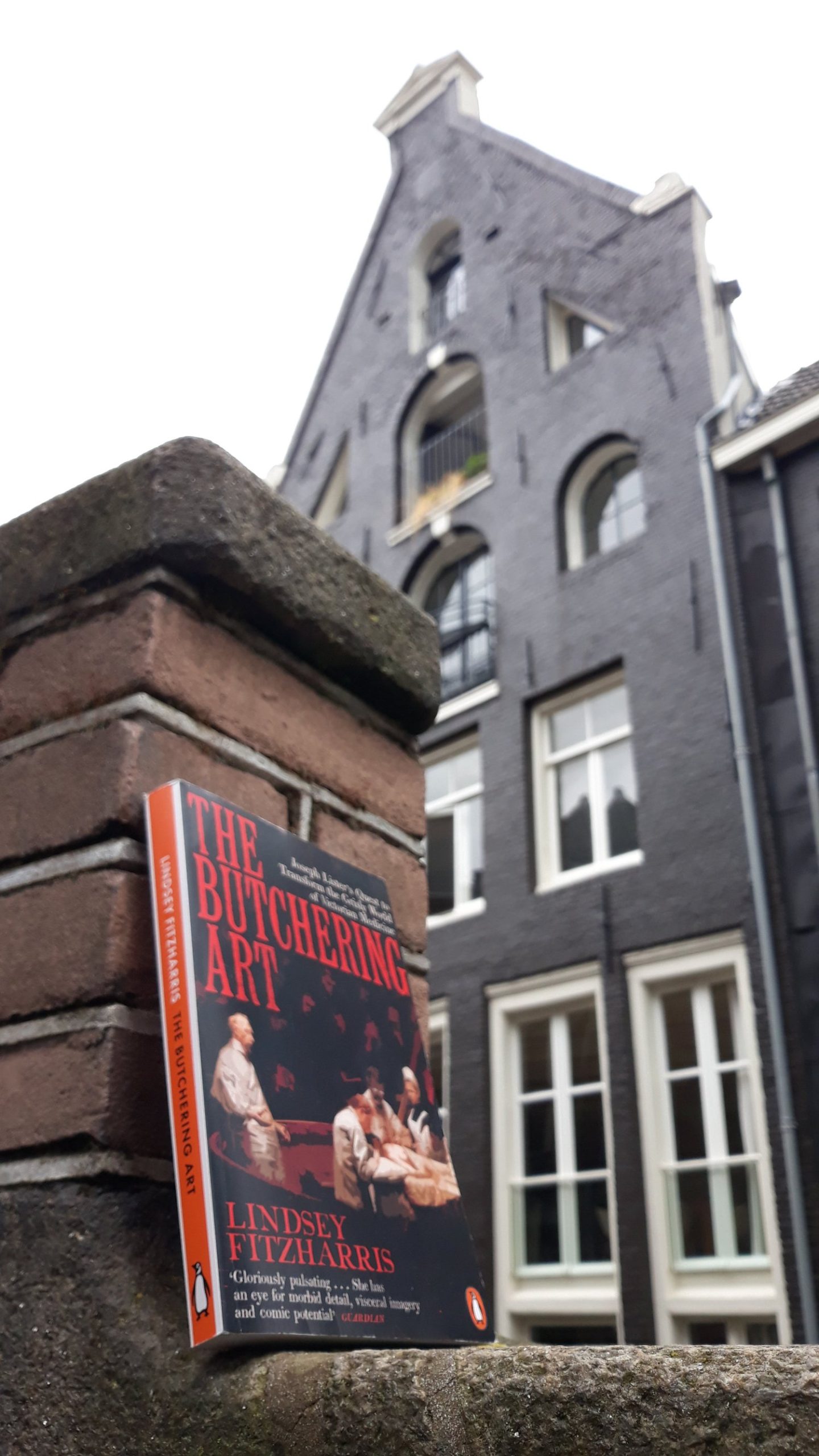

The history of medicine is fascinating. Theories and ideas that are currently accepted, or even taken for granted, can take a long time to become mainstream, or even accepted. The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine by Lindsey Fitzharris provides an insightful account into the history of infection, sepsis and (the lack of) hygiene during surgery. Nowadays we think of operating theatres as sterile, clean spaces. You have to only look at a hospital-based medical drama to learn that scrubbing your hands ferociously before surgery, and changing your scrubs afterwards is of utmost importance.

Yet, this was not always the case. The word operating theatre reveals the history of surgery as a spectacle with an audience. Fitzharris eloquently describes the role of the surgeon in the 1800s and how the work of Joseph Lister has had a tremendous impact on surgery as we know it. Lister was a scientifically inclined man who tried to understand what causes post-surgical infections. Lister worked at a time where bacteria were not considered to be, or known to be, the source of infections. Bad air was thought to be the cause, and as a consequence surgeons did not think to change their wardrobe between operations, or even to wash their hands. Notably, it was thought that pus was part of the healing process, not a dangerous sign of sepsis.

In Lister’s time, hospitals and operating theatres were dangerous places for the sick to be. Many died of infections, so often caused by the hands of surgeons. Surgery, as Fitzharris’ title alludes to, was a butchering art and particularly painful before the invention of anaesthetics and sedation.

“In the 1840s, operative surgery was a filthy business fraught with hidden dangers. It was to be avoided at all cost. Due to the risk, many surgeons refused to operate altogether, choosing instead to limit their scope to the treatment of external ailments like skin conditions and superficial wounds. (…) Surgery was always a last resort and only done in matters of life and death”

— The Butchering art (Fitzharris, 2017, page 5)

Nowadays surgery is seen as a great tool to heal and safe lives. But a lot of deaths pave the way for the field of surgery as we know it.

Joseph Lister was born in 1827 and died in 1912. Fitzharris shows Lister’s journey developing germ theory. He discovers that disinfecting wounds is instrumental in preventing infections and post-operative death. This was not a straightforward or linear journey, not the least because Lister had to overcome his own pre-existing beliefs regarding the cause of sepsis. As mentioned earlier, pus was thought to be a healthy part of the healing process, not a sign of danger. Building on the work of Louis Pasteur, Lister experimented with ways to prevent infection. Having designed a system to do so, it was no easy convincing the wider medical community to uptake this method. Antisepsis, the method of using chemicals, called antiseptics, to destroy the germs that cause infections. as developed by Lister, thankfully, was implemented by the medical community in due course, and it has impacted how surgeries are done to this day.

Joseph Lister’s work ethic and method also shows how ideas are not thought of in silo. Instead, good scientific work builds on the work of others, and Lister credited the work of others that help him reach the conclusions he reached. We might look back at surgery in Victorian times with horror, but I would love to be a historian of the future, looking at our present medical practices to see what conventions have become terribly outdated.

The writing style of medical historian Fitzharris is accessible and entertaining, and I have already requested her more recent book The Facemaker which tells the story of the pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies, from my local library.

To learn more about Lindsey Fitzharris visit her website.

Leave a Reply