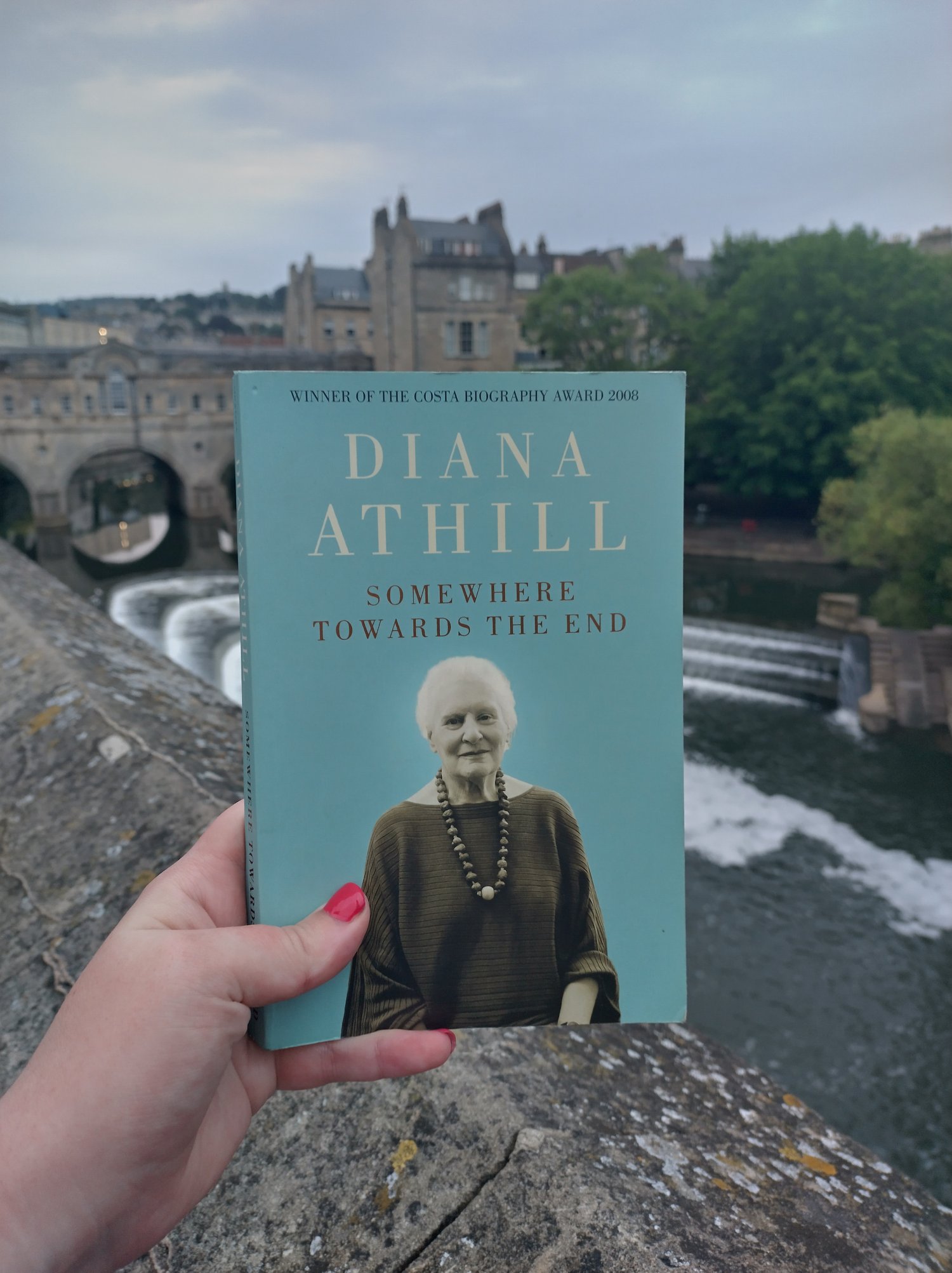

The photo of ‘Somewhere Towards the End’ was taken in front of Pultney Bridge and the Weir in Bath, England. I visited Bath this July and found a copy of this book in a charity shop. The house I used to live during my time in Bath is pictured as well. I used to spend a lot of time in the gutter outside my window, drink in hand, overlooking the weir. Bath is very much an important part of my personal becoming.

A month from now it will be a decade since I left the country of my birth, the Netherlands, to pursuit a PhD at the University of Bath in England. I spent four years here, thinking about the meaning of ‘home’ and tried to understand experiences of ageing and dying from the perspective of older people themselves. This thinking accumulated in a thesis Unpacking Home: Ageing and Dying in Older Age in the southwest of England, a piece of writing, like most doctoral students, I have a love/hate relationship with. During this time I came across the work of sociologist Richard Jenkins on identity. He argues that,

identity can only be understood as a process. As ‘being’ or ‘becoming’. One’s social identity- indeed one’s social identities, for who we are is always singular and plural- is never a final or settled matter.

Jenkins (1996, page 4).

This idea of becoming is very appealing; throughout our lives from birth until death we are always in a state of becoming. Living new experiences and thinking about life in new ways. I found this notion particularly pertinent in relation to older people, who are often solely thought of as people in decline, as walking medical problems, as people in need of assistance and care. Middle age is often as the epitome of personhood; both children and older people are measured against the qualities of middle aged people who are thought of as people’s ‘true selves’. Children are developing to become this ‘true self’, older people have gone passed this peak and are more and more moving away from this. This thinking is simplistic and favours middle age for no apparent good reason. Hence why I favour the notion of becoming.

This becoming we see in Diana Athill’s Somewhere towards the end (2008). This poignant memoir is but one example of how older people still develop. Yes, Athill describes losses and bodily decline, but there is also space for new adventures, new (sexual) relationships, and new experiences. Her writing at times does betray the ingrained sense that older age is predominantly about decline:

“It is so obvious that life works on terms of species rather than individuals. The individual just has to be born, to develop to the point at which it can procreate, and then to fall away into death to make way for its successors, and humans are no exception whatever they may fancy. We have, however, contrived to extend our falling away so much that it is often longer than our development, so what goes on in it and how to manage it is worth considering. Book after book has been written about being young, and even more of them about the elaborate and testing experiences that cluster round procreation, but there is not much on record about falling away.”

Diana Athill (2008, page 10)

In my thesis I am very critical of our cultural obsession with dying at home, particularly as no one seems to unpack what this means a communal understanding of ‘home’ is assumed. I was, and still am, pondering why good dying experiences seem to have been reduced to a singular space, and why this space is favoured over others. Similar to seeing our lives and identities on an everlasting road of becoming, so too do I see ‘home’ as an active process, homemaking if you will. It is something we actively create not passively have.

As people are living and dying for the first time they cannot fully know what they want towards the end, instead, they increasingly get a better picture of what they don’t want. And this is strongly influenced by the dying experiences of those around us. Athill is no exception, as her personal experience of seeing her parents die peacefully brought comfort for when the time will come for her:

“The reassurance concerns the actual process of dying. There cannot be many families in which so many people have been lucky in this respect as mine has been. Even the least lucky were spared the worst horrors (which can, of course and alas, be very bad). My maternal grandmother had to endure several months of distressing bedridden feebleness owing to the prolonged heart failure, but she had a daughter to help her through it at home and that daughter was able to report that the attack which finally killed her was a good deal less disagreeable than some of those that she survived.”

Diana Athill (2008, page 71).

Athill is also keenly aware that death is ultimately inevitable: ‘Whatever happens, I will get through it somehow, so why fuss?’ (page 75).

Ultimately, this memoir is more about living than about dying, but the two always go and in hand. Athill died in 2019, aged 101. I am curious to read her 2015 memoir ‘Alive, Alive Oh!: And Other Things That Matter’ to see whether her reflections and observations about her life and inevitable death have changed since she penned down ‘Somewhere towards the End’, and I hope that my personal becoming will be as fortunate as the one described in this memoir.

Leave a Reply