This month I am taking part in Memoir March. Memoirs are an interesting genre of books. Memoirs are based on people’s life stories but memories are not fixed entities, instead feelings towards, and interpretations of, memories might change over time. Furthermore, whilst memoirs are based on ‘true events’, sometimes the truth needs to bend to fit the narrative. Memoirs around grief, dying and loss appear to be sprouting everywhere and I was spoiled for choice when selecting books to read this month.

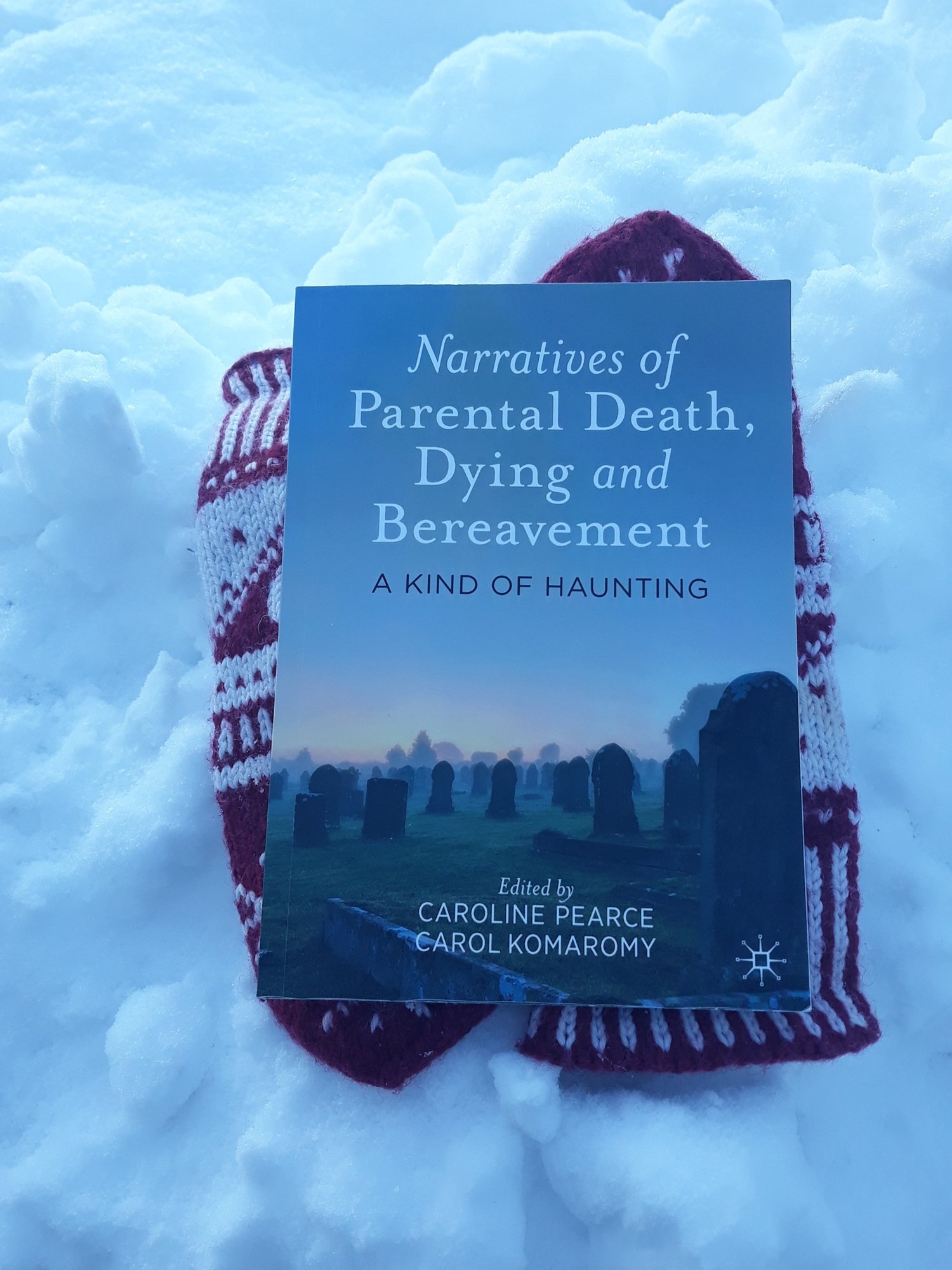

Since it is not a statistic that is being kept, it is hard to say at what age people lose their parents and experience parental bereavement. In the UK it is estimated that by the age of 16, 1 in 20 children will have lost one or both of their parents. When I was conducting my research for my master’s on parental loss in young adulthood in the Netherlands I was unable to find any data about the amount of Dutch people that lose a parent in childhood. As my first ever research project was on parental bereavement, I was very excited to get my hands on the edited volume Narratives of Parental Death, Dying and Bereavement: a kind of haunting.

Narratives of Parental Death, edited by Caroline Pearce and Carol Komaromy, consist of 9 chapters in which 8 academics reflect on their personal experience of losing a parent. I found this a very interesting read, not the least because I personally know most of the people who contributed a chapter. But because of the nature of academic work and meeting people mainly at conferences, I have to admit I have never thought about them as entities with parents. I have connected these people to their academic research and ideas and although this is, ironically, death for all contributors, death scholars still shy away of bringing their own experiences into the narrative. This is exemplified most strongly in the chapter written by Douglas Davies, as he writes about the divide between the personal and the professional which, in the first instance, made him reluctant to contribute to this collection.

Grief memoirs, and sharing stories on loss, death and grief is becoming increasingly popular. Co-editor and chapter contributor Caroline Pearce, who has lived most of her life without her parents, is critical of this story telling and writes:

“During my PhD field work on recovery following bereavement, I became aware of the powerful discourse in the literature that claimed telling one’s story could assist in recovery from grief. Indeed, it was claimed to be healing and restorative. Yet I began to feel fatigued over what felt like a proliferation of stories, and specifically the use of stories as a means of liberation. Instead, I started to wonder whether it might be better to say nothing at all’ ”

— Pearce Page: 179.

Luckily, Pearce and Komoramy did decide to focus a collection of essays on the universal experience of the death of a parent. While we might not know when this will happen, this experience will happen eventually to all of us (and this is perhaps one of the ‘hauntings’ the title is referring to).

“The embodiment of parents into our identity suggests that the stories belong to us; we are writing about the experience of parental death. At its simplest level, we are telling our own stories. We have no way of knowing what stories our parents might have told”

— Pearce and Komaromy Page:26

The edited volume Narratives of Parental Death consist of 9 chapters, and 8 academics reflect on their personal experience of losing a parent. I found this a very interesting read, not the least because I personally know most of the people who contributed a chapter. But the nature of academic work and meeting people mainly at conferences, I have to admit I have never thought about them as entities with parents. I have connected these people to their academic research and ideas and although this is, ironically, death for all contributors, death scholars still shy away of bringing their own experiences into the narrative. This is exemplified in the chapter written by Douglas Davies, as he writes about the divide between the personal and the professional which, in the first instance, made him reluctant to contribute to this volume.

The volume beautifully demonstrates the complex relationships we might have with our parents. We all come from parents, but this does not automatically mean we get along or have good relationships with them. We can be embarrassed by our parents. We can no longer be in touch with them. I read Jenny Hockey’s chapter on her father’s death the same day I attended an online seminar where I saw she was one of the attendees. It felt very meta ‘seeing’ her there when I just finished reading something so intimate and personal. I also had to restrain myself not to hijack the question part of the seminar by asking Jenny about this chapter. (I am aware I am switching to first names, where I have to date always referred to the surname of authors…) Jenny talks about her father’s death and how he died of a fistula that led to him being slowly poisoned. This poisoning led to him telling what Jenny adorably calls ‘untruths’, which made their father-daughter relationships increasingly complicated.

I am glad Pearce and Komaromy decided to gather a cackle of academics and invite them to share their stories of parental bereavement, as this offers a new and important layer of this type of bereavement, and adds to the literature in the field of death, dying and bereavement studies. This edited collection will speak to so many people and I am therefore happy to report that the editors fought for an affordable price point for this book as the paperback retails for £25 (and the e-book is even cheaper) -and yes for academic publishing this is a bargain.

If you have read this book, do share your thoughts on it below in the comments, and if you want to order the book directly from the publisher click here.

Leave a Reply