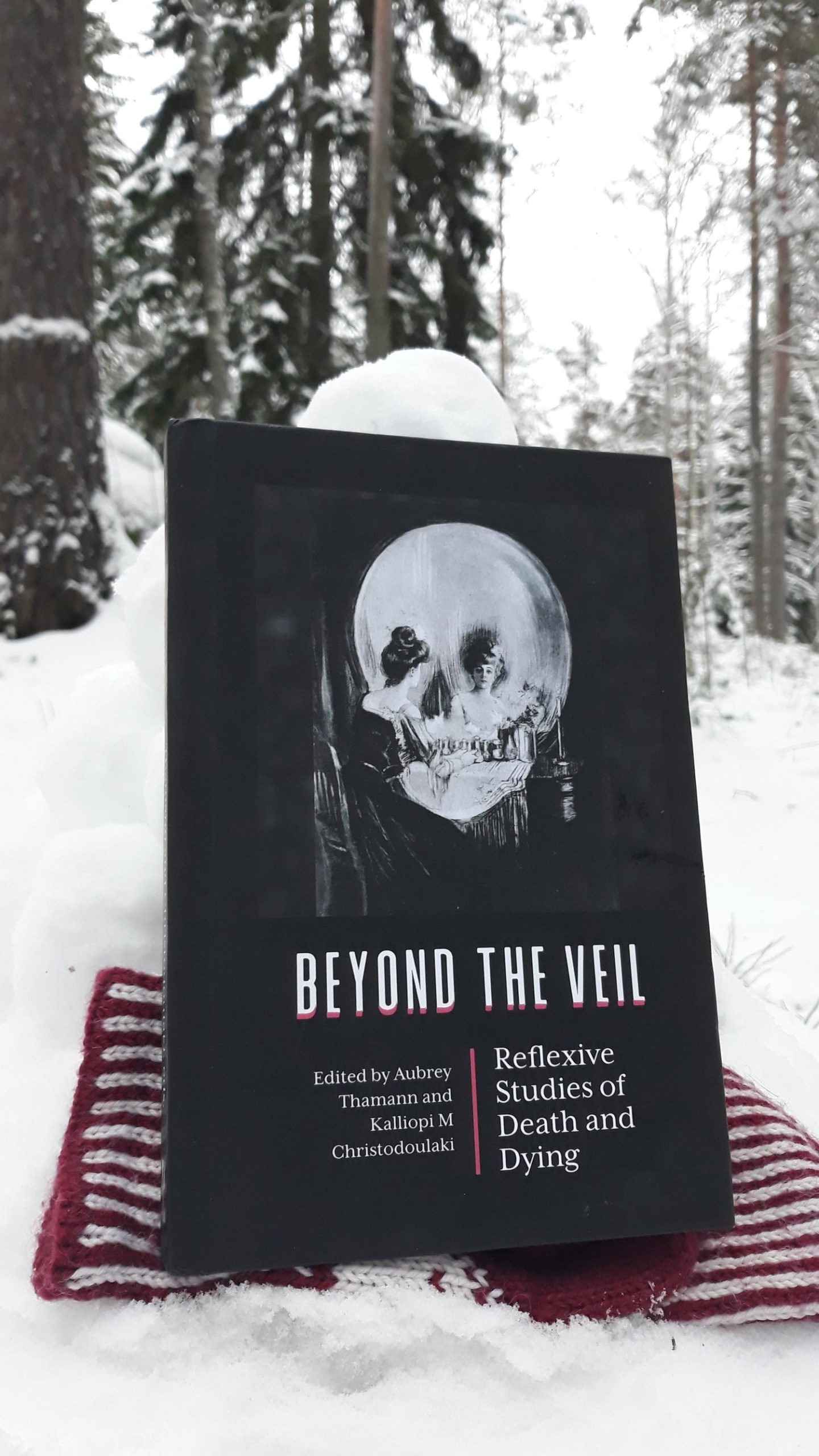

Beyond the veil: reflexive studies of death and dying is a wonderful edited collection I encourage any death scholar to read. I will be the first to admit, however, that the price of these kinds of books will make it inaccessible for wider readership in the general population (and admittedly also within academic circles) but I do hope a potential paperback edition can give it the audience it deserves. The hardback version of Beyond the veil is retailing for £99 or $135; the e-book is significantly cheaper at $34,95 (and a discount code is available below).

In this edited collection, editors Aubrey Thamann and Kalliopi M Christodoulaki brought together a group of death scholars “whose experiences with death profoundly shaped their work”(p.1). The starting point of this edited collection is the subjectivity, or the lived experiences, death scholars bring to their work. Arguably, researching the field of death, dying and bereavement, more openly reveals the subjectivity of the researcher, as they are both confronted with their own mortality and will have experienced death in varying degrees in their own circle.

“Any analysis of the topic cannot be decontextualised; yet almost all academic studies of death ignore the scholar’s relationship to death and mortality. This is short-sighted, as we must all inevitably grapple with loss and mortality as we examine cultural responses to death”

— Thamann and Christodoulaki, page:2

It is important that researchers are open about their background and the experiences that bring them to a certain field of study. Some will come to death studies because of life experiences, for others it is more happenstance or plain curiosity. But where you come from and how you embody the world has a strong impact on how you relate with existing theories on death and dying.

Both the absence and the omnipresence of death in the lives of people who study death will profoundly shape their work, yet these kinds of reflections and accounts are often dismissed or discouraged in academic writing and considered to be ‘navel-gazing’. I have written about this issue as well in a paper published in Death Studies.

The book is divided in four sections: 1. Delaying Death, 2. Caregiving, 3. Confronting death and 4. Memorialization and 11 scholars have written a contribution. I will not summarise each contribution but will highlight a chapter from each section.

The first section talks about people who like to stave off dying. In his chapter Immortality and Existential Terror: learning the language of living forever, Jeremy Cohen talks about his research with people who hope for radical longevity and life extension. In other words, his research focuses on people who aspire to immortality. Cohen researchers a community of people that want to live forever, and he notes that he did not understand this urge until his own near-death experiences and the death of his great-uncle. Cohen suggests that personal experiences and opinions of researchers can colour and (mis)interpret the beliefs and actions of groups they do not fully understand or align with. He writes:

“There exists a multiplicity of identities and responses in the face of death, both for a researcher and subject. The singularity of every death can result in a mistranslation of the experience of the other by anthropologists. The desire of immortality may map perfectly onto theories about death denial but tell us nothing about the actual experience of death. I do not know if members of People Unlimited are denying death, but I do know that their living among the cult of death creates active engagements with life”

— Cohen Page:45

The second section of the book explores how two death scholars cope with death and dying in their own personal life. In her chapter Living, Caring, and Dying: Music and the House of Endless Losses Carina Nandlal discusses caring for her mother who is living with dementia and is coming towards the end of her life. Nandlal talks about the gender dynamics in caring for ageing relatives and how her brother is not affected in the same way as her and her sister are. She, like so many carers, is both working and caring for her mother. One of the things that decreases the hardships of caring is remembering her mother’s love for music. Music had been central in her mother’s life and subsequently in how she had been raised herself:

“When caring for a dying loved one causes life to seem bereft of meaning and my own identity to dissipate, music can validate my emotions and invite me back to connect with my mother based on our shared experiences. Music has become central to the new rituals of our lives”

— Nandlal Page: 58

Listening to music with her mother reinforces their relationship and overcomes the absence of words and speech. This chapter is a poignant example of how you rarely know what goes on in the lives of researchers alongside their research.

Researchers will have different attitudes towards entering a field of research. Ekkehard Coenen describes notions of closeness and distance in studying the field of death. In his chapter “What has the Field done to you?” Researching Death, Dying and Bereavement between Closeness and Distance, Coenen talks about his research interests in funeral homes in Germany. Before researching death, Coenen had very little personal experience with death, but he decides to fully emerge himself in the field. He takes this emerging further than some and even decides to train as a funeral director. He argues that this insider knowledge and ‘becoming one with the field’ gave him a level of insight he would not have gained otherwise.

The last section of the book offers four chapters that look at memoralization. Kami Fletcher has had ample experience with death and dying in her personal live. Her chapter Long Live Chill: Exploring Grief, Memorial, and Ritual within African American R.I.P T-shirt culture vividly talks about her personal experience with the commemoration ritual of R.I.P T-shirts. The chapter is complemented with photos of both herself, and her relatives wearing commemorative t-shirts. Fletcher notes that these t-shirts, whilst having an origin in rap and gang mourning culture, have become an important part of public mourning in African American culture more generally:

“There is power in R.I.P t-shirts because for Black people it is an important part of the support system, memory-making, and experience-sharing after death”

— Fletcher Page: 211

Fletcher, a historian by training, moves towards more ethnographic methods to understand the ritual and meaning behind these t-shirts. The death of her nephew is a big inspiration for this chapter, and because of this bereavement Fletcher is very much part of the ritual she studies.

Recently Fletcher has spoken extensively about this ritual in an episode of the Death Studies Podcast which you can listen to below.

All the contributions in this edited collected show the importance of understanding researchers’ personal involvement in the field and how their background and lived experience shape the ways in which they approach the topics they study. Contributions show that lived experience can shape the topics people study and that personal loss can aid in understandings research findings. I personally hope more volumes like this will emerge and that death scholars will continue to reflect about their subjective involvement in researching death as this makes for a richer field of study.

You can order the book here. You will receive a 25% discount on the e-book with the code DRG25 (valid until the end of March 2022)

Leave a Reply