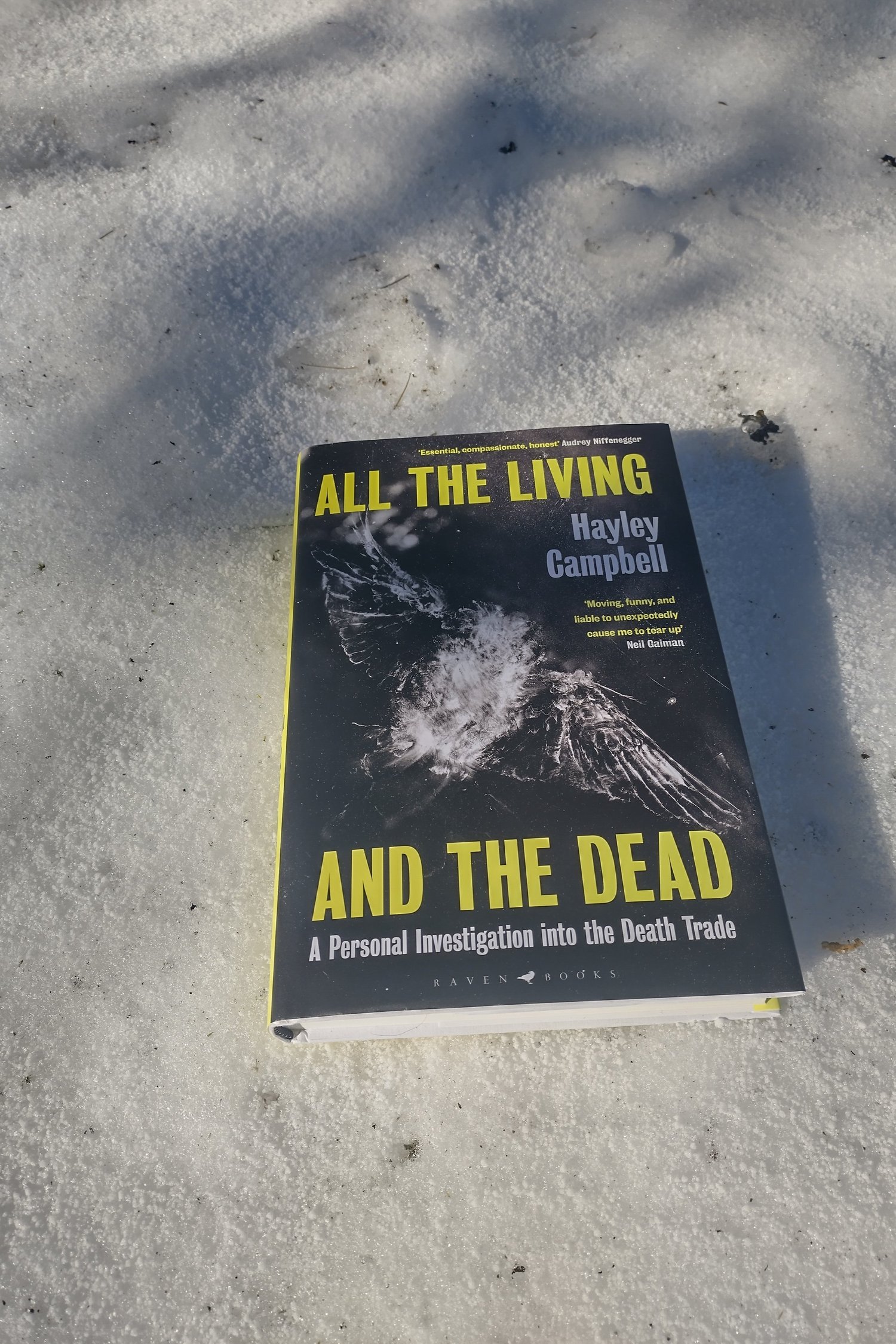

In All the living and the dead journalist Hayley Campbell shines a light on death-related jobs that often stay hidden in the margins. The book lifts the lid on the behind-the-scenes of the people that (sometimes quite literally) do the groundwork. Some jobs, like funeral directors and celebrants, might be considered obvious death work, but other jobs such as grave diggers, death mask sculptors, bereavement midwives and executioners are professions that people might not readily think of. In these pages, readers, like me, might discover deathy professions they had never heard of.

I highly appreciate Campbell’s rational for writing this book: Campbell has been fascinated by the phenomenon her entire life. She is a kindred spirit if you will as I, too, have been simply fascinated by death my entire life. For me this interest has let in an academic career, blog and podcast that hone in on the subject, for Campbell this has resulted in a wonderfully engaging book based on the fundamental question of how people working in the death industry cope with working with death and dying on a daily basis.

“The Western death industry is predicated on the idea that we cannot, or need not, be there. But if the reason we’re outsourcing this burden is because it’s too much for us, how do they deal with it. They are human too. There is no us and them. It is just us”

— All the Living and the Dead (2022) page 7

This book reminds me of various The Death Studies Podcast conversations with practitioners working in the field of death, including What Remains author and undertaker Ru Callender and emergency planner and writer of When the Dust Settles Professor Lucy Easthope. Campbell’s book highlights the range of amazing people that make a living out of death and the important role (visibly or not) they play in people’s lives.

A suggestion made by Funeral Director Poppy Mardall early in the book has stayed with me: the first dead body you witness should not be someone you love. Instead, this witnessing should be the body of a stranger, so you can separate the shock of seeing death from the shock of grief. As I have recently become part of a research project that centres children’s views on death and dying, I am inspired by Poppy’s wish to invite schoolchildren to the mortuary, so they can become gently acquainted with death. This tender witnessing reminds me of stories my grandma would tell me: As a child, when a death would occur in her village, they would knock on the door of the house that contained the dead person and ask if they could ‘have a look’. After a bit of a peek, they would then go home and continue business as usual.

Personally, all the dead bodies I have witnessed in my life have been friends and relatives (including said grandma). My first dead body was that of my uncle who died when I was 8. I vividly remember that I had to plea with my mother to be able to see his body (I similarly had had to plea to be able to visit him in hospital. Due to a brain tumour, he had lost the ability to open his eyes and my parents thought I would find this disturbing. At some point I was allowed to visit, and I was always angry that I was running behind a few visits compared to my parents). When I watched my uncle in his coffin, I placed a necklace made up of silver letters of my name separated by coloured plastic beads on a string in his coffin. I sometimes wonder what future archaeologists will make of this; likely only finding these letters if they’d dig up the grave. I agree with Poppy that it would be good to few the bodies of strangers as an entry point to death. I also think viewing my uncle’s body did not traumatize me, it just visually confirmed that my uncle was in fact dead. Subsequently I have found myself always having the need for this visualization; a quick mental image to record that the person is in fact gone.

I found reading the words of retired funeral director and embalmer Ron Troyer moving for various reasons. Firstly, as embalming is not a practice I am familiar with beyond reading about it, I am ambivalent about how I feel about it. His suggestion that it is not a violent practice is an interesting one, and his reflections on what embalming can mean for those who stayed behind give me food for thought. Secondly, as Ron is the father of John Troyer, who I know from my time in Bath and who has featured in a very powerful episode of The Death Studies Podcast, which consists of two interviews; one ‘typical’ interview and a follow-up interview in which John reflects on his mother’s death and talks about how this interview has been one of the final things she has listened to in her life. It is moving to read about people who you know by extension. Both Ron and Jean Troyer have died and it is heart-warming that some of their knowledge and wisdom will live on in this book.

For author Campbell, the research and experiences that were part of writing this book show how unprepared people can be to certain responses in relation to death and dying. In her case, the presence of a dead baby in a bathtub in a post-mortem room is an image that continues to haunt her. It does prompt cognitive dissonance: why would a baby need a post mortem. Sadly, in this case it was warranted, and revealed to Campbell her own limits in what she thought she was able to observe as a mere bystander. Baby loss and baby death are very challenging topics, and I will write about some baby loss memoirs later this year.

Campbell’s writing is engaging and inviting; her sincere interest in the topic and the people she speaks to is palpable. I have learned there is a person making face masks of the dead, an anatomy pathology technician who calls themselves a ‘corpse servant’ (I have been trying to find this quote in the book whilst writing this so partly worried I misread that, so do correct me if I’m wrong!). There is the story of the executioner on death row in the US, stories of death cleaners, disaster specialists and so much more- just go read this book!

To learn more about Hayley Campbell visit her website.

Leave a Reply