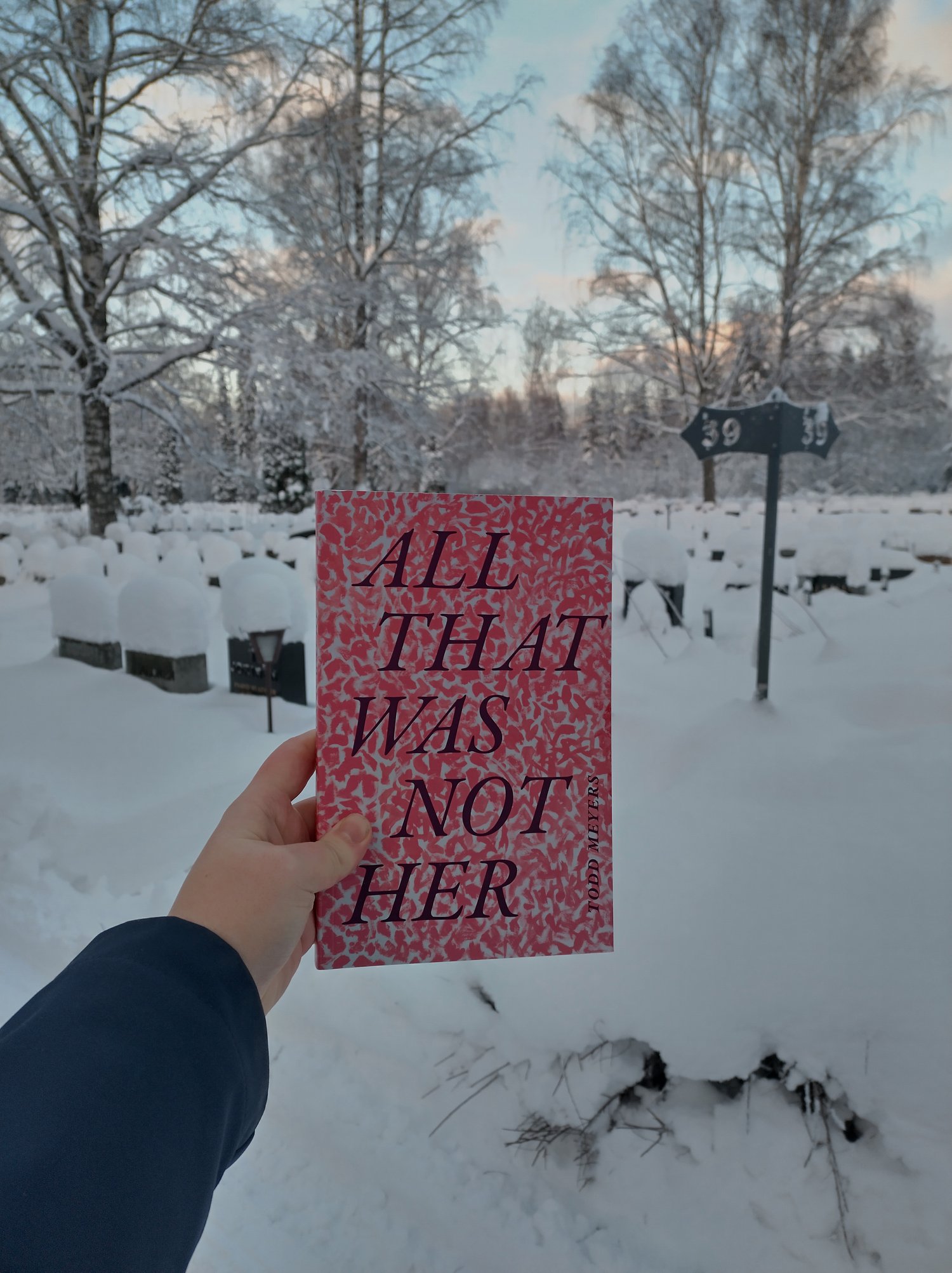

All that was not her by anthropologist Todd Meyers is unlike any other ethnographic account I have ever read. The text provides a wonderful blend of creative and poetic writing. The writing is playful yet thought-provoking, akin thoughts written out in fieldnotes. The fragmented writing style underscores the notion that researchers never really fully understand or ‘know’ the lifeworlds of those they study. Anthropologists can be in the lives of their interlocutors for many years and still not uncover all the layers that make up a person.

The focus of the book is Beverly, an African American woman who was part of Meyers research on chronic illness and caregiving. They had a complicated relationship and at some point lost touch. When Meyer tries to rekindle the relationship, he discovers that Beverly died.

All that was not her are sketches of a white male anthropologist trying to make sense of his (research) relationship with an interlocutor, and to what extent physical death changes this relationship. The narrative moves between passages on She/Her (Beverly), I (Meyers) and He (the anthropologist, or Meyers looking from a distance at himself). The account can be read as a cross-over or blend between fiction, non-fiction, anthropology, philosophy and ethics.

I wish I could put words to the quality

of difference in Beverly’s story of herself

and my story of her.

I wish I could say plainly what distinguishes one horizon from the next, because maybe that would explain why certain images assert themselves more than others. By now I have accepted that the protagonist of this story is between us. Maybe what I am looking for is the quality of connection between certain images, between moments of uneven intensity. I believe some images are worth returning to over others, reasons for which I cannot often explain, but they share the same line in the middle of the image that divides the sea and sky.

–All that was not her (Meyers, 2022 page 128)

In essence, anthropological writing is storytelling. Anthropologists often swim in their fieldnotes, interview data and participant-observation. They are left with a puzzle, which on the one hand will provide an answer to the research question they have asked themselves, yet on the other hand offers even more questions about the complexities of social life, identities and ‘knowing’. Can we ever really ‘know’ another person, and if so, how do we capture their ‘essence’ in the written word? Do people have an ‘essence’?

Death scholars move themselves more readily in the world of death and the dead, and will perhaps expect participants to die during the course of their study. In the paper “Doing death”: Reflecting on the researcher’s subjectivity and emotions, I have written about the complexities of emotions when a research participant dies, and notions of subjectivity in death research in general. Yet, this paper only scratches the surface of what role the death of a participant, or interlocutor, plays in the lives of the researcher. June, who died during the course of my PhD, has ceased to exist, yet my thinking on topics of ageing, dying, homemaking and later life has not halted. Furthermore, my more experimental writing, my grieve for her and all the conversations I have had about her post-death, will likely never be published or made public.

It is therefore refreshing to read Meyers messy account on Beverly (or who he thinks Beverley may or may not be). Meyers grapples with Beverly’s physical death, yet Beverly continues to be part of his thinking, his personal life and is in memory still very much alive.

There is a fable he tells himself.

It is a story about a person who experiences physical death but remains a living, breathing subject in the writing and thought of the anthropologist, even when that subject, strictly speaking, no longer lives or breaths. It is the morbid trick of anthropology, to traffic between life and death through scholarly acts of resuscitation, planting the subject in an afterlife where they can be returned to again and again.

– All that was not her (Meyers, 2022, page 64)

I hope Meyer’s work paves the way for more experimental writing in anthropology. We are taught that people’s lives are messy, non-linear and rarely straightforward, but when putting pen to paper we try to tame this jumble of often contradictory beliefs and produce a coherent narrative, an ethnography with a clear beginning, middle and end. This mimics other types of scientific writing, yet does not adequately capture the social world. So anthropologists (or any writer for that matter), editors and publishers: please embrace this, and also allow for anthropologists who aren’t white and male to experiment with this format. (Side note: if you know of any works that are like Meyer’s please leave a comment!)

If you find yourself reading this review thinking “but I am not an anthropologist, is this the book for me”, I’d like to say: if you have any interest in human beings and the social world, and if you like to observe the world, than you are, training or no training, a budding anthropologist. People interested in the cross-over of poetry, narrative, philosophical thinking, relationships, anthropology and to what extent physical death changes the relationship between people, will get a lot out of this book.

To learn more about Todd Meyers click here. To order the book directly from Duke University Press click here.

Leave a Reply