In November 2019 Usman Khan travelled to London to attend a prison education conference at Fishmongers’ Hall. Khan had been convicted of terrorism-related offences when he was just 20, and spent 8 years in a high-security prison. His temporary release license did not allow for travel to London, he had to be given special permission to be able to attend this conference. At some point during that November day, he retrieved a fake bomb vest and knives, his actions that day wounded three people and killed two: Saskia Jones and Jack Merritt. Khan was shot dead by London police.

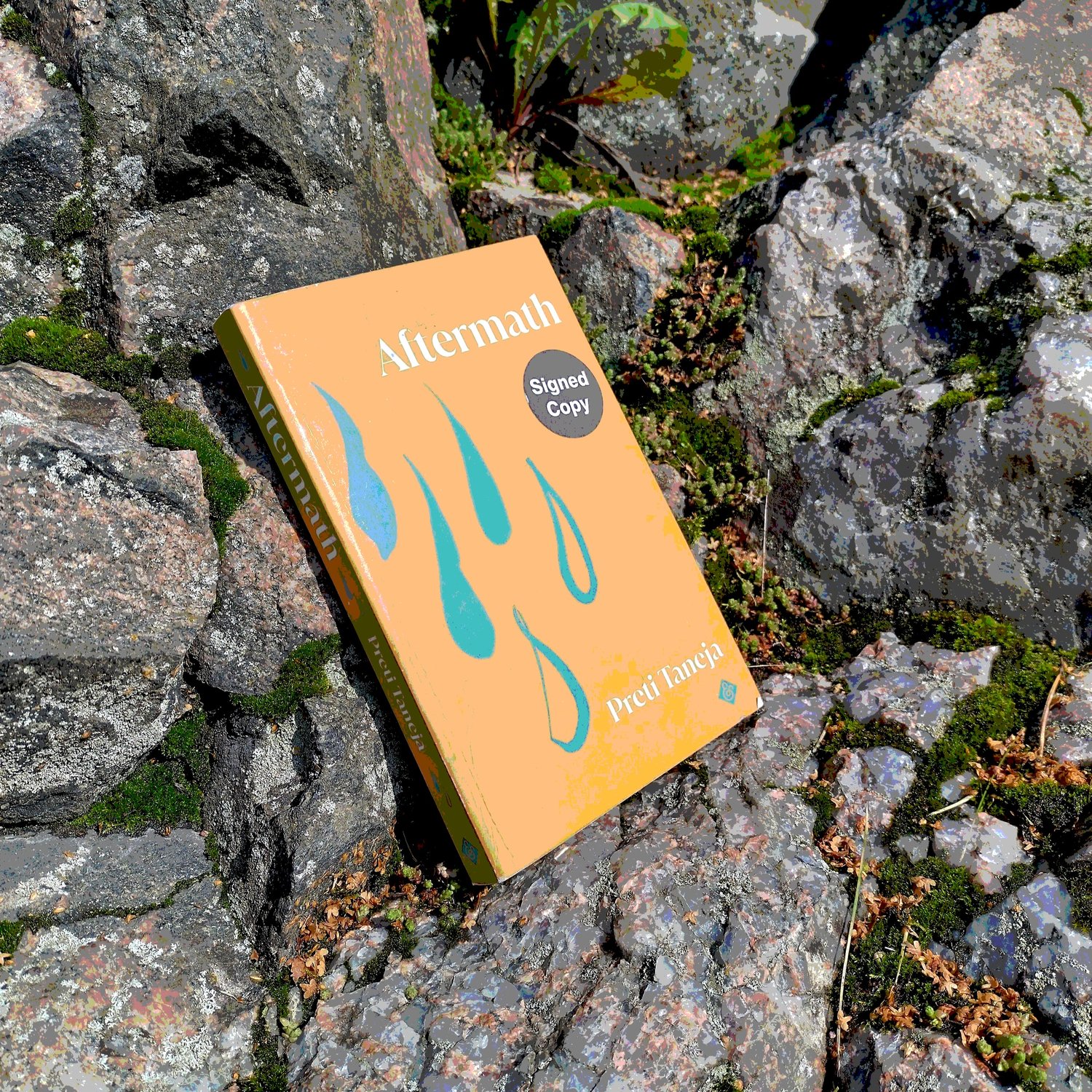

Preti Taneja taught creative writing to Khan in prison. Jack Merritt was one of her colleagues. Aftermath (2022) is a profound and deeply moving account on the complexity of grief, on serendipity, on racial relations, on control and punishment, on responsibility. Did Taneja play any part in these events? Did her teaching affect his behaviour? Why wasn’t she at that conference that day? Should she have been? Could all of this have been prevented?

I was in London that November day. More precisely, at some point I was on the other end of London Bridge. From January 2019 until December 2022 I was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Surrey researching cancer care in prison. I have visited multiple prisons, both high and low security, and interviewed numerous people with cancer in prison, healthcare professional both inside as well as outside of prison, and prison officers to understand to what extend cancer diagnosis, treatment and care differ compared to those living in the general population.

In November 2019, I conducted a phone call with someone who had a coordinating role in providing healthcare in prisons. As people with cancer in prison are a minority, it is difficult to pinpoint which prisons have people with cancer living in their care. We spoke about access to patients and consent- I remember apologising for some of the noise as I was currently standing inside London Bridge station. My memory does betray me in that I don’t fully know what I was doing that day in London, and since I lost access to my email address and accompanying diary, I can’t verify this information anymore. I do remember returning to my flat in Guildford, waking up the next day to several missed calls from this healthcare person, who was terribly relieved I finally returned her call and that I hadn’t been at Fishmongers’ Hall, despite just being just across the bridge. ‘ I remember you saying you were at London Bridge, so I was worried’- At the time I remember being so touched that someone I had only had two phone conversations with was so worried about my wellbeing.

This interaction reminds me of the words of disaster management Lucy Easthope from her book When The Dust Settles that it is not surprising to be present at disasters in your life – or in my case, to be near them. My potential proximity does, however, in no means compare to the nearness and the complexity of Taneja’s involvement.

Survivor’s guilt is felt by those who were invited but did not go to the event, or were not in the same room as where the attack took place; or did not fight the attacker; or were standing near but could not help those hurt; or even those close enough to look into the attacker’s eye, and speak to him, and say stop. Because we did not die, we can suffer that sense that we have less legitmacy to grieve it seems without end

Preti Taneja (2022, page 35)

Taneja’s creative writing in Aftermath is thought-provoking and challenging and deals with notions of responsibility, boundaries of grief and loss. Who is allowed to feel what for whom. She demonstrates the power of the full stop and how sentences change meaning if you don’t end with this tiny symbol

Her experience leads to literature on grief and loss and her experience mirrors that of others who have experienced so-called disenfranchised grief. A term she had no use for until this event.

Months later, I will learn the phrase disenfranchised grief – a particularly difficult form of loss to overcome. The majority of cases involve personal decisions made. Such loss often creates a sense of shame or guilt […] making it difficult to openly mourn, discuss or cope with the actions that have created the loss. I think of the decisions I made, to teach. The vulnerability of the creative writing room, the requests I made so I could keep the students safe never answered by authorities. The sense I had of each student. Who was posturing, who needed approval, who was writing trauma? All of them.

Preti Taneja (2022, Page 37-38).

Building on the work of Judith Butler and ideas developed in Precarious Life (2001) Taneja importantly notes that trauma is not a singular event affecting an individual but has much wider implications, which are reflected in the way we write about trauma:

Following 9/11 Judith Butler writes that we use the narrative I after violent, traumatic events, to make up for the decentring wound we have suffered (the italics are mine – an implicit question as to whom we include). Drawing on Black feminist abolitionist thinking, Butler’s is a call to write away from this patriarchal form, this authority- to think about the queerness and solidarity of grief in community. Trauma cannot be written, or survived, in the first person singular

Preti Taneja (2022, page 158)

Taneja’s writing moves between the first person singular, the third person singular and plural forms.

Taneja’s writing touches on many important themes: belonging and notions of identity; trying to ‘fit in’ in British society, a society where no one is surprised that someone who looks like you, will eventually end up in prison.

These are the options before you: repeat after me

High, lauded achievement/everyday assimilation/prison/

All options require a death.Preti Taneja (2022, page 53).

Having lived in the UK for four years, I was definitely othered- on any official paperwork I needed to tick the box ‘White other’, as opposed to ‘White British’. I received many questions about ‘where my accent came from’ (which to this day I do not know if this was a compliment or a slight). But there was always relieve that I was from Amsterdam, that fun city across the pond, so I must be a fun person as well. And thank god I wasn’t from Poland.

As certain groups are overrepresented in UK prisons, I was partly surprised that in our cancer research none of our participants were anything other than White (both White British and White Other…) but perhaps this speaks to the fact that Black and Brown British people are taken less seriously in doctor’s offices.

Aftermath has touched me on multiple levels; it is an important critique of British society and the prison system, its writing style original and challenging. It is a text I will return to in the future, both to look deeper into its messages and its style.

Preti Taneja is a writer and activist. Her debut novel We That Are Young (Galley Beggar Press, 2017) is a translation of Shakespeare’s King Lear, set in contemporary India. It won the Desmond Elliott Prize for the finest literary debut novel of the year and was listed for awards including the Folio Prize, the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize and the Prix Jan Michalski, Europe’s premier award for a work of world literature. Aftermath is her second book. To learn more about Taneja visit her website.

Leave a Reply