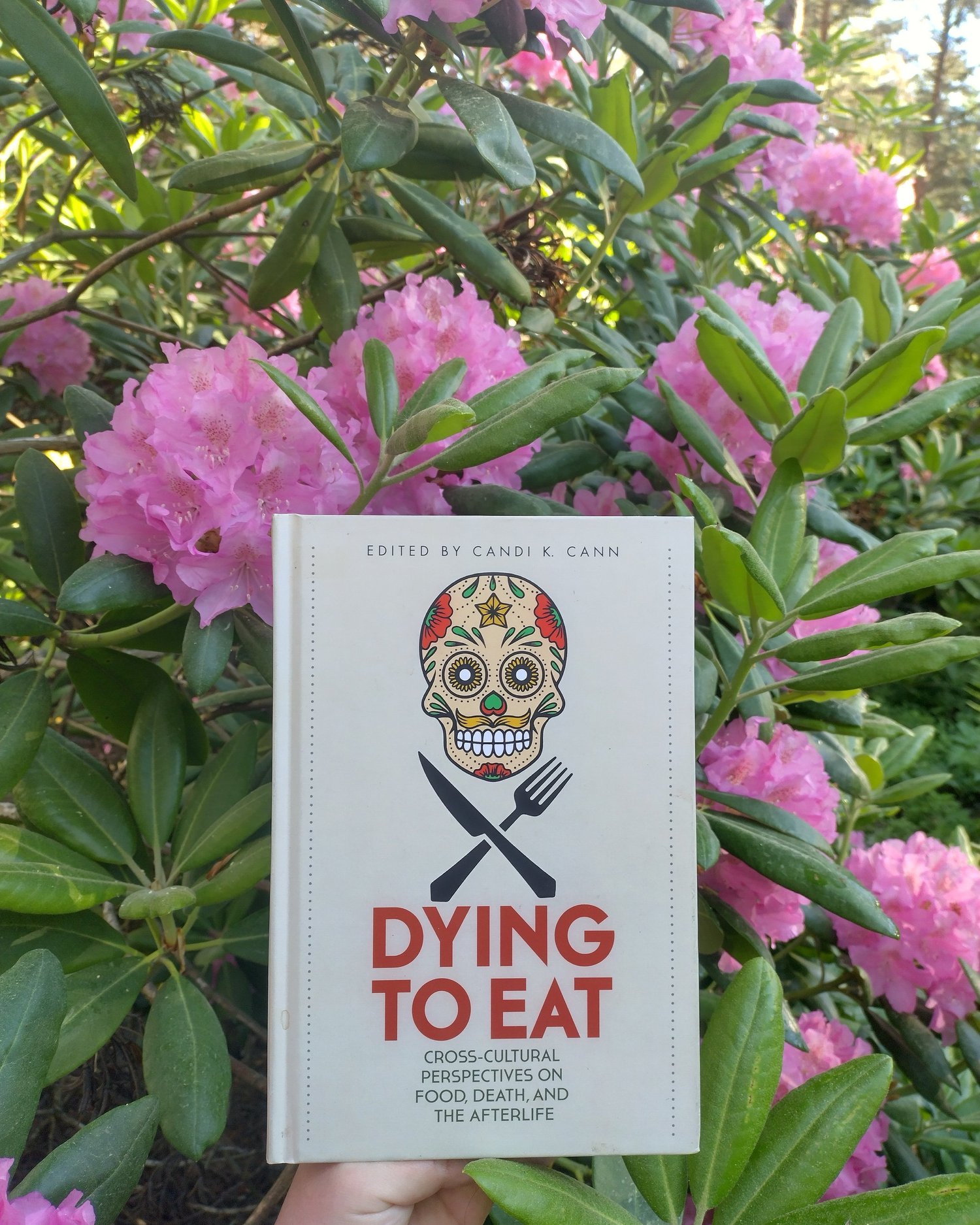

You can tell a lot about cultures, or countries by their food habits. The way various groups deal with death and dying equally tells plenty about social organisation, beliefs and rituals. If you combine academic interest in the two, you get something like the appetizing edited collection Dying to Eat: Cross-cultural perspectives on food, death and the afterlife, edited by Candi Cann. In this collection the reader is taken across the globe to better understand the role of food in funerary rituals and memorialization.

“Food is a central actor in funeral feasts, bereavement rituals, and memoralization practices, and it remains an enduring (and often overlooked) part of the material world of grief. Food has played a major role in funerary and ritualized funerary practices since the beginning of humankind”

— Dying to Eat. Cann, 2018: page 3 .

If, like me, you grew up in a place where food is rather functional, and the best cuisines available in your country are due to a problematic colonial history, you can find yourself feeling envious of other death food cultures and rituals. In the Netherlands, funerals are streamlined events, and people typically are served coffee and cake after the funeral ceremony. It might be a sandwich, or a snack favoured by the deceased. There are no funeral feasts or fancy meals. It’s quick and easy, as people need to get on with their lives.

I love how there is some playfulness and creativity in this volume, which start at the table of contents. There is no introduction but a ‘starters’, the acknowledgments are ‘digestifs’, the contributors are listed as ‘chefs’ and the index is referred to as ‘condiments’. Each chapter also includes a recipe of the funeral food described, making it part death book part cookbook.

There are eight chefs in this edited collection and they have written about customs in China, Korea, the United States, Morocco, South-Africa, Mexico, and in Judaism. The book is divided in two parts Dining with the Dead and Eating After: Food and Drink in Bereavement and Remembrance.

In the Dining with the Dead section, the chapters consider how food is used to not just remember deceased loved ones, but as a means to actively reintegrate the deceased in everyday life. For example, Emily S. Wu explores Han Chinese ancestral worship and how food is shared between the living and the dead:

“Foods for the clan ancestors are cooked but minimally processed, barely edible to start with, and especially stale and tasteless after sitting on the ancestral shrine for hours. Rather than disposing of the meat offerings, frugal Han Chinese take them back into the kitchen to make them into dishes to serve at the family gathering that follows”

— Wu. 2018: page 17.

Wu suggest that food is used to transcend the boundary between the living and the dead. Twice-cooked pork is one of the dishes that is created after the pork has been offered to the ancestors. In this way the living and the dead are able to share a meal.

Jung Eung Sophia Park, similarly talks about how food practices continue bonds with ancestors in Korea. Food habits transcend religious communities, and Park notes that eating rituals are part of death rites in both Catholic and Buddhist communities.

“Growing up in Korea, I often witnessed food placed on the threshold or at the front gate of the house. The offerings were composed of simple foods, such as a bowl of rice, rice wine, and rice cake, along with money and traditional Korean straw shoes. Koreans believe that the souls of the dead, especially parents and ancestors, visit their families on holidays and on the anniversaries of their dead for reunion.”

— Park, 2018: page 41.

The last chapter in the first section of the book will appeal to anyone with a sweet tooth. Cann’s chapter explores the role of sugar in funeral feasts and memorialization practices. While Halloween, the Day of the Dead and Qing Ming (described by Cann as a sort of Chinese Memorial day akin to American Thanksgiving and Memorial Day wrapped up in one) are three different celebrations, they share a love of sugar and sweet goods. Cann notes, however, that in Mexico and China, food is used as a bridge to the afterlife, yet during the American celebration of Halloween, the sugary delights are solely used to nourish the living.

The second part of the book Eating After looks at the ways in which food plays a role after the funeral, and in remembering the dead. Graham shows how in the American South funeral food is an important way to keep the dead alive. Not only is the most recent deceased remembered at these food gatherings, the food that is cooked has a way of resurrecting the long-dead.

“The handing down and sharing of funeral food recipes, lore, and memories both help maintain strong family and community bonds and stave off indivial social death”

— Graham, 2018: 89.

For as long as Maw Maw Wallace’s chess pie (the recipe is also published in the book!) is being handed down to new generations, and baked for funerals, the memory of Maw Maw Wallace will live on. In this way, Southern funeral feasts serve both as individual and collective spaces of remembrance.

Oualaalou, in his chapter, talks about how a Moroccan food staple, couscous is essential in Moroccan funeral feasts. A simple food item is shared with not only relatives, but also with strangers, to form a larger community in times of loss.

“A viewing is not considered necessary because the funeral feast offers a chance for mourners to gather together to remember the deceased. That is also why the family welcomes strangers attending funerals. These strangers are considered part of the community and might have heard about the deceased during his or her life. Their attendance during and after burial is their way not only of paying respects, but also of expressing their sympathies to the family”

— Oualaalou, 2018, page: 140.

In these two examples of the American South and Morocco we see how funeral food is used for community building, and sometimes even for the extension of communities. Graham’s chapter shows how special funeral food recipes are used on these occasions whereas Oulalaalou outlines how everyday food can be as powerful in bringing people together.

I will leave the rest of the chapters for readers to discover, but suffice to say is that if you have an interest in food, death and ritual practices, than this is definitely the book for you!

Cann has brought together a tasteful collection of authors that shed light on the various ways in which food can serve not only as nourishment, but as powerful symbolic tools to both connect the living and the dead. I look forward to future scholarly work that explores the world of food in relation to death, dying and the dead, as this book definitely left me wanting more. I would also love to hear from readers about their particular food customs they do in times of loss, so please leave a message below if you wish to share!

Bon appétit!

To order Dying to Eat directly from the publisher, visit their website.

Leave a Reply